European companies face chip crisis after China’s export ban on Nexperia: Read how Trump’s diktat to Dutch govt threatens to shut down EU’s own automobile production

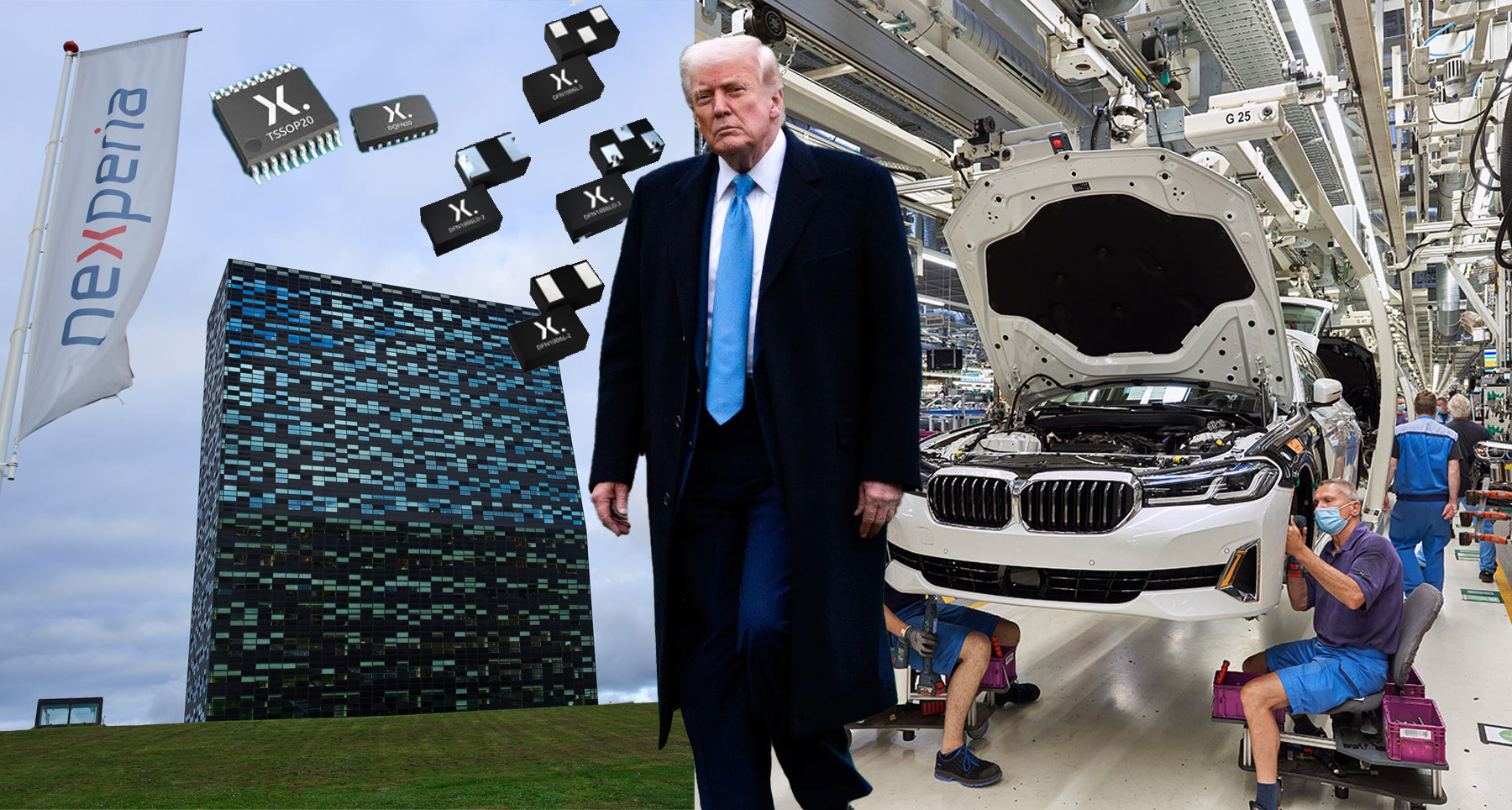

The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) on 16th October issued a statement calling for a quick resolution of critical chip supply disruptions from a major chipmaker caused by major geopolitical factors. Nexperia, a Dutch chipmaker, said that it can’t guarantee supply of European car manufacturers after China imposed an export ban in retaliatory action, potentially disrupting the automobile industry in Europe. ACEA said that it deeply concerned by potential significant disruption to European vehicle manufacturing if the interruption of Nexperia chips supplies cannot be immediately resolved. This dramatic escalation of global trade tensions was caused by the Dutch government’s seizure of Chinese-owned semiconductor firm Nexperia after U.S. threatened to sanction the company for its Chinese links. The takeover of the company, and removal of its Chinese CEO, triggered a retaliatory export ban from China, threatening to halt vehicle production across Europe. This chain of events, rooted in geopolitical pressures from the United States, has left European automakers scrambling for alternatives as supplies of critical chips dwindle. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) has issued an urgent call for resolution, warning of imminent disruptions. Here is how American pressure on global trade, increased many fold under Donald Trump’s presidency, is causing disruptions across the oceans. Nexperia and its strategic importance Nexperia, headquartered in Nijmegen, Netherlands, is a leading producer of high-volume semiconductors used in automotive, consumer electronics, and industrial applications. The company manufactures older generations of semiconductors in large numbers, not the latest chips like GPUs and AI processors. These “mature” chips power essential components like electronic control units in vehicles, making them indispensable for modern manufacturing. The company is also one of the world’s largest makers of simple computer chips such as diodes, transistors, and MOSFETs (Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors, a type of semiconductor device used for switching and amplifying electronic signals) used in large numbers in almost every electronic and electrical equipment. These relatively simple chips perform unglamorous but absolutely vital functions in vehicles and other machinery. The company makes around 50 billion components annually. Originally spun off from Dutch giant NXP in 2017, Nexperia was acquired by China’s Wingtech Technology in 2019 for approximately $3.6 billion. This acquisition created a dual ownership structure, while Wingtech, a Shanghai-listed company with significant Chinese state ties, holds majority control, including through its CEO Zhang Xuezheng’s stake, Nexperia maintains its operational independence with a global footprint. This setup has allowed it to leverage European innovation and Chinese manufacturing scale, but it has also exposed the company to geopolitical risks, as Western governments are increasingly worried about Chinese influence over critical technologies. Even after the Chinese acquisition, Nexperia has operated with research, development, and manufacturing sites across the Netherlands, Germany, Britain, the United States, and Asia, including China, employing over 14,000 people and generating billions in revenue. Its vertically integrated supply chain includes front-end wafer fabrication primarily in Europe with sites in Hamburg, Germany, and Manchester, UK, and back-end assembly and testing in Asia, notably in Guangdong, China, alongside facilities in Malaysia and the Philippines. For ease in understanding, this can be compared with Tata’s upcoming two semiconductor plants in India, while its Gujarat plant will fabricate the wafers, the final semiconductor chips will be assembled, packaged and tested at its Assam plant. While Tata’s production extends into different states in India, Nexperia’s production extends in different continents. This hybrid model of Nexperia, design and initial production in Europe and then with cost-effective finishing and assembly in Asia, has made Nexperia a key supplier, producing over 100 billion components annually. However, the reliance on cross-border flows has made it vulnerable to trade disruptions, particularly in the automotive sector, where its chips are integral. The company’s dual European-Chinese identity has made it a flashpoint in the U.S.-China tech war. Nexperia’s chips are vital for Europe’s automotive sector, which has already endured chip shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflicts. Losing access to these components could cripple production lines, as alternatives require months of homologation and testing. U.S. pressure leads to Dutch government takeover The saga began escalating earlier this year amid heightened U.S. scrutiny of Chinese influence in global technology supply chains. U.S. officials, under the Trump

The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) on 16th October issued a statement calling for a quick resolution of critical chip supply disruptions from a major chipmaker caused by major geopolitical factors. Nexperia, a Dutch chipmaker, said that it can’t guarantee supply of European car manufacturers after China imposed an export ban in retaliatory action, potentially disrupting the automobile industry in Europe. ACEA said that it deeply concerned by potential significant disruption to European vehicle manufacturing if the interruption of Nexperia chips supplies cannot be immediately resolved.

This dramatic escalation of global trade tensions was caused by the Dutch government’s seizure of Chinese-owned semiconductor firm Nexperia after U.S. threatened to sanction the company for its Chinese links. The takeover of the company, and removal of its Chinese CEO, triggered a retaliatory export ban from China, threatening to halt vehicle production across Europe.

This chain of events, rooted in geopolitical pressures from the United States, has left European automakers scrambling for alternatives as supplies of critical chips dwindle. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) has issued an urgent call for resolution, warning of imminent disruptions. Here is how American pressure on global trade, increased many fold under Donald Trump’s presidency, is causing disruptions across the oceans.

Nexperia and its strategic importance

Nexperia, headquartered in Nijmegen, Netherlands, is a leading producer of high-volume semiconductors used in automotive, consumer electronics, and industrial applications. The company manufactures older generations of semiconductors in large numbers, not the latest chips like GPUs and AI processors.

These “mature” chips power essential components like electronic control units in vehicles, making them indispensable for modern manufacturing. The company is also one of the world’s largest makers of simple computer chips such as diodes, transistors, and MOSFETs (Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors, a type of semiconductor device used for switching and amplifying electronic signals) used in large numbers in almost every electronic and electrical equipment. These relatively simple chips perform unglamorous but absolutely vital functions in vehicles and other machinery. The company makes around 50 billion components annually.

Originally spun off from Dutch giant NXP in 2017, Nexperia was acquired by China’s Wingtech Technology in 2019 for approximately $3.6 billion. This acquisition created a dual ownership structure, while Wingtech, a Shanghai-listed company with significant Chinese state ties, holds majority control, including through its CEO Zhang Xuezheng’s stake, Nexperia maintains its operational independence with a global footprint.

This setup has allowed it to leverage European innovation and Chinese manufacturing scale, but it has also exposed the company to geopolitical risks, as Western governments are increasingly worried about Chinese influence over critical technologies.

Even after the Chinese acquisition, Nexperia has operated with research, development, and manufacturing sites across the Netherlands, Germany, Britain, the United States, and Asia, including China, employing over 14,000 people and generating billions in revenue. Its vertically integrated supply chain includes front-end wafer fabrication primarily in Europe with sites in Hamburg, Germany, and Manchester, UK, and back-end assembly and testing in Asia, notably in Guangdong, China, alongside facilities in Malaysia and the Philippines.

For ease in understanding, this can be compared with Tata’s upcoming two semiconductor plants in India, while its Gujarat plant will fabricate the wafers, the final semiconductor chips will be assembled, packaged and tested at its Assam plant. While Tata’s production extends into different states in India, Nexperia’s production extends in different continents.

This hybrid model of Nexperia, design and initial production in Europe and then with cost-effective finishing and assembly in Asia, has made Nexperia a key supplier, producing over 100 billion components annually. However, the reliance on cross-border flows has made it vulnerable to trade disruptions, particularly in the automotive sector, where its chips are integral.

The company’s dual European-Chinese identity has made it a flashpoint in the U.S.-China tech war. Nexperia’s chips are vital for Europe’s automotive sector, which has already endured chip shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical conflicts. Losing access to these components could cripple production lines, as alternatives require months of homologation and testing.

U.S. pressure leads to Dutch government takeover

The saga began escalating earlier this year amid heightened U.S. scrutiny of Chinese influence in global technology supply chains. U.S. officials, under the Trump administration, viewed Nexperia’s Chinese ownership as a national security risk, fearing potential technology transfers or supply manipulations by Beijing in a crisis. Given that Nexperia is benefiting from major researches in Europe and USA, the Trump admin believe China can access such intellectual property through the company.

In June 2025, Washington warned Dutch authorities that Nexperia risked being added to the U.S. Entity List, a blacklist restricting exports of American technology, unless changes were made, particularly regarding the company’s CEO, Zhang Xuezheng, who holds a controlling stake in Wingtech.

Then in September, the U.S. govt issued a new rule expanding its Entity List, to automatically include subsidiaries owned 50% or more by a company already on the list. The action was aimed at stopping export of critical technology and equipment to Chinese companies. This new rule applied to Wingtech, Nexperia’s parent company, bringing Nexperia under indirect U.S. export control.

Along with this American pressure, concerns over governance issues at Nexperia also existed, including allegations of mismanagement such as forcing unnecessary wafer orders worth $200 million, firing executives who protested, and conflicts of interest tied to Zhang’s other business interests.

On 30 September, the Dutch government took over the control of Nexperia invoking the rarely used 1952 Goods Availability Act, a Cold War-era law allowing intervention in private companies to secure critical goods during emergencies. The govt cited worries about the possible transfer of technology to Nexperia’s Chinese parent company Wingtech.

This “highly exceptional” move placed Nexperia under temporary external management, suspending Zhang from his roles and transferring control to a court-appointed administrator. The Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs cited “serious governance shortcomings and actions” that threatened the continuity of Nexperia’s operations and the safeguarding of vital technological knowledge on European soil. Officials argued that without intervention, Europe could face shortages in semiconductors, jeopardizing economic security, especially in the automotive industry.

The Dutch govt move was preceded by an Amsterdam commercial court order to suspend Wingtech CEO Zhang Xuezheng from his position as executive director at Nexperia. The court appointed Dutch businessman Guido Dierick to take Zhang’s position with a “deciding vote”, and transferred control of almost all of Nexperia’s shares to a Dutch lawyer for management.

The takeover does not involve outright nationalization, instead, it restricts major decisions on assets, personnel, or business changes for up to a year, ensuring production continues while blocking potential relocations or tech transfers to China.

Wingtech denounced the action as “excessive intervention driven by geopolitical bias,” emphasizing Nexperia’s compliance with local laws and its local employment contributions. The company said in a filing to the Shanghai stock exchange that its control over Nexperia would be temporarily restricted due to the Dutch order and court rulings, affecting decision making and operational efficiency.

This move echoes prior U.S.-influenced actions, such as the 2022 forced sale of Nexperia’s UK wafer fab in Newport due to security concerns.

China’s retaliatory export ban and its impact on Europe

Beijing responded swiftly and decisively to the Dutch intervention. On October 4, 2025, just four days after the takeover, China’s Ministry of Commerce issued an export control notice under its Export Control Law, prohibiting Nexperia China, the company’s subsidiary in Guangdong, and its subcontractors from exporting certain finished components and sub-assemblies to Nexperia and its affiliates outside China.

The ban specifically targets products manufactured in China, framing it as a countermeasure to “unilateral” foreign actions that undermine Chinese enterprises’ rights. This was not a blanket prohibition on all Nexperia activities but a targeted restriction on outbound shipments of completed semiconductors, effectively severing a critical link in the company’s global operations.

“The Chinese Ministry of Commerce issued an export control notice prohibiting Nexperia China and its subcontractors from exporting specific finished components and sub-assemblies manufactured in China,” the firm said.

This has caused major disruptions to Nexperia’s chip supplies to its customers Europe, because of intricate supply chain even though it is based in Europe. The company employs a “fab-lite” model where front-end processes, like wafer fabrication and initial chip design, take place at its European facilities in Hamburg and Manchester. Raw silicon wafers are fabricated at these facilities. These wafers are then shipped to assembly sites in Asia, including Guangdong, China, for packaging, testing, and final assembly into usable chips. Essentially, the company makes the circular wafers in Europe, which are then cut into and packaged as individual chips.

Once completed, these finished products are exported back to Europe or directly to global customers, including automotive suppliers. China plays a pivotal role in this chain, handling a significant portion of the high-volume, low-cost assembly, estimated at up to 30-40% of Nexperia’s total output, due to its advanced facilities and cost efficiencies.

The export ban disrupts this flow by halting shipments from China to non-Chinese Nexperia entities or customers. As a result, even though Nexperia’s European fabs continue operating, they cannot receive back the assembled chips needed for final distribution. This creates a bottleneck, stockpiles of unfinished wafers pile up in Europe, while finished chips remain stranded in China.

For European carmakers, this means a sudden shortfall in critical components like power management ICs and transistors, which are not easily substitutable due to automotive qualification standards requiring rigorous testing that often take 6-12 months. Nexperia has other Asian sites in Malaysia and the Philippines, but these lack the capacity to fully compensate for the Chinese output, leading to delays and shortages.

The ban’s precision, allowing domestic Chinese sales but blocking exports, amplifies pressure on Europe without broadly harming China’s economy and its growing automobile industry, which has increased its share in Europe significantly. This means, while European carmakers can’t produce their vehicles, Chinese carmakers like BYD and MG can increase their exports to Europe.

Nexperia confirmed the restrictions in a statement, noting active engagement with Chinese authorities for an exemption.

ACEA’s Distress Signal

On October 10, 2025, Nexperia notified automakers and suppliers that it could no longer guarantee chip deliveries due to Chinese export ban, with current stocks expected to last only a few weeks. The company outlined a sequence of events that makes them no longer being able to guarantee delivery of their chips to the automotive supply chain.

We are deeply concerned by potential significant disruption to European vehicle manufacturing if the interruption of Nexperia chips supplies cannot be immediately resolved.

— ACEA (@ACEA_auto) October 16, 2025

On 10 October, #automobile manufacturers and their suppliers received notice from Nexperia outlining a… pic.twitter.com/RW8qveXCng

As a result, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association issued a distress note on 16th October, saying that European automotive suppliers cannot build the parts and components needed to supply vehicle manufacturers without these chips, and therefore it threatens production stoppages. It stated, “While the industry already sources the same types of chips from alternative players on the market, the homologating of new suppliers for specific components and the build-up of production would take several months, while current stocks of Nexperia chips are generally predicted to last only a few weeks.”

ACEA Director General Sigrid de Vries said, “We suddenly find ourselves in this alarming situation. We really need quick and pragmatic solutions from all countries involved.”

Major carmakers also sounded alarms. BMW said its supplier network is impacted but there is no immediate production stops. The company said it is closely monitoring risks. Volkswagen echoed similar concerns, noting Nexperia’s role in its supply chain without current disruptions. Mercedes-Benz and Stellantis are assessing impacts and developing mitigations, though details on direct exposure vary. Even suppliers like Bosch, which uses Nexperia chips, are on high alert.

The Dutch government has realised the gravity of the consequence of its actions, and Minister for Economic Affairs Vincent Karremans said that he wants to find a solution with China regarding the Chinese export ban on Nexperia chips. Karremans is optimistic that the talks will progress positively.

The crisis extends beyond Europe, with some sections warnings that U.S. auto production could also be affected, highlighting the global interdependence of supply chains. The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, representing a large group of US automakers, has warned of potential supply issues.

Trump’s Dictates Causing Disruptions in Europe

Although the issue emerged due to the actions of Dutch and Chinese governments, at the heart of this turmoil are the aggressive trade policies of U.S. President Donald Trump, whose second term has intensified the U.S.-China tech war. Trump’s administration has prioritised “decoupling” from Chinese technology, imposing entity list designations and pressuring allies in Europe and Asia to restrict Chinese-owned firms. In December 2024, Wingtech was added to the U.S. Entity List as a security concern, barring U.S. exports without approval. Then in September 2025, Nexperia was added to the list, along with demands to remove its CEO which was accepted by the Dutch.

USA and Trump’s dictates, framed as protecting national security, have forced European nations into uncomfortable positions, balancing U.S. alliances with economic ties to China. The Dutch takeover, while justified domestically on governance grounds, was explicitly accelerated by U.S. threats, leading to China’s ban and the ensuing chip crunch. This has disrupted Europe’s automotive sector, already grappling with tariffs, weak demand, and competition from Chinese EVs.

This is just one instance of how Trump’s unilateral approach is undermining global trade stability, turning allies like the EU into collateral damage in his broader agenda against Beijing, and Russia. For example, his insistence on not purchasing Russian oil and gas has already put lots of pressure on Europe, traditionally heavily dependent on Russian energy sources.