I saw The Bengal Files and here is my message to Hindus as a Jew: If you wish to learn from us, don’t learn from our political blindness

I saw The Bengal Files (TBF) in Hyderabad, where star actress Pallavi Joshi said it would be available with English subtitles. This 200-minute film is aimed to be epic, a clarion call for a tipping point in Indian history, a goal largely achieved by the previous film in this trilogy, the Kashmir Files (TKF). I interviewed Pallavi when TKF came out, and I was curious to see how this film compares to the previous sensation. To my best recollection, this film is even more gut-wrenching and disturbing than the previous. The violence is equally graphic but far greater in scale: TBF portrays a flashflood of murderous rampage unleashed on Kolkata on Aug. 16, 1946, when M.A. Jinnah and The Muslim League declared Direct Action Day with the senior local assistance of Prime Minister of Bengal H.S. Suharwardy, later to become PM of Pakistan. The subsequent Noakhali Riots of Oct.-Nov.1946 also feature prominently in our film at its shocking climax. I speak as a videshi outsider, an Israeli researcher of India with many beloved Kashmiri and Bengali friends, but no family there or direct recollection of either tragedy in Kashmir or Bengal. But then again, as an Israeli, a graduate of the Religious Zionist education system which currently contributes disproportionately to the IDF fighting force in Gaza and its casualty tally, and as a grandson to my grandfather and namesake Yeshaya Hanft who’s family and entire village were massacred by the Nazis, watching this epic film was a loaded experience in a different way. It offered many comparisons to take note of and reflect upon, from gratitude for the security offered to me by the State of Israel, to rage at predicament of my Bengali friends, to theological reflections from Jewish classical literature on the ways of creating meaning out of collective tragedy and grief to amass the strength to rise from them. It is on these deeper themes that I wish to dwell on in this essay. I will recap various parts of the plot and assume that readers have already watched the film or intend to soon. A Brief Recap Shiva Pandit (Darshan Kumar) is a CBI officer sent to Kolkata to investigate the disappearance of a young woman. He is summarily notified that all evidence leads to Sardar Hussain (Saswata Chaterjee), an MLA from Murshidabad, but Sardar is so powerful, nobody will investigate him, and so, case closed. Shiva is indignant and refuses to comply. His lead informant is a senile elderly woman, Bharati Banerjee (Pallavi Joshi) whom Gita had been living with. As the film progresses Maa Bharati begins to talk, and recalls not only recent events, but lengthy flashbacks from her youth. In these flashbacks the young Bharati (Simrat Kaur) is a revolutionary, who barely survives the carnage of Direct Action Day with the help of her guardian angel, a young Sikh warrior, Amar Singh (Eklavya Sood). Together the power couple assist Gopal Patha (Sourav Das) in organizing Hindus for self-defense and retaliation, and subsequentially continue to be active in the struggle for impendence, revolutionary journalism, and the frantic scramble for self-defense amid the evermore threatening postures of the Miyar Fauj, a local Muslim mob led by the young Gholam Sarwar,(Namashi Chakraborty), Pir of Daira Sharif and self-styled Pakistani revolutionary and thug. In this cinematic framework, the flashbacks from the chaotic violence of Partition are projected by Bharati’s flashbacks into the plot set in present-day West Bengal, in a grand repeat of Bengali history: the same perpetrators, same enablers, same victims, same crimes, the same desperate heroes and the same collective ineptitude. “But there will be communal riots!” was the excuse for not stopping Gholam long before he led his mob at Noakhali and remains the excuse for privileging his next incarnation, Sardar, over his hapless victims. “Is Bengal the new Kashmir?” asks the refrain of the twice-tormented Kashmiri refugee, Shiva Pandit. This movie cries out for a negative answer. Who are the Villains? While watching this film it becomes obvious that there is another villain beyond the parallel characters of Gholam-Sardar: Gandhi. From the first moment, Gandhi is portrayed as a holy fool. When approached nervously by young Bharti posing her deepest thoughts on the choice between violent and non-violent struggle, his response is that he must go now and milk the goat, and if she wants she can join. In the same symbolic scene Gandhi has a live snake carefully carried away without being harmed, caring for the viper more than for Bengal. When he empathically states that non-violence will lead to justice, Bharti asks what will happen if it does not lead to justice and is left unanswered. In a later scene, Gandhi is laying on a bed fasting for the end of the Calcutta Killings and collecting weapons from Hindus who organized themselves for self-defense. When Gopal Partha arrives, he asks Gandhi what will happen if the M

I saw The Bengal Files (TBF) in Hyderabad, where star actress Pallavi Joshi said it would be available with English subtitles. This 200-minute film is aimed to be epic, a clarion call for a tipping point in Indian history, a goal largely achieved by the previous film in this trilogy, the Kashmir Files (TKF). I interviewed Pallavi when TKF came out, and I was curious to see how this film compares to the previous sensation.

To my best recollection, this film is even more gut-wrenching and disturbing than the previous.

The violence is equally graphic but far greater in scale: TBF portrays a flashflood of murderous rampage unleashed on Kolkata on Aug. 16, 1946, when M.A. Jinnah and The Muslim League declared Direct Action Day with the senior local assistance of Prime Minister of Bengal H.S. Suharwardy, later to become PM of Pakistan. The subsequent Noakhali Riots of Oct.-Nov.1946 also feature prominently in our film at its shocking climax.

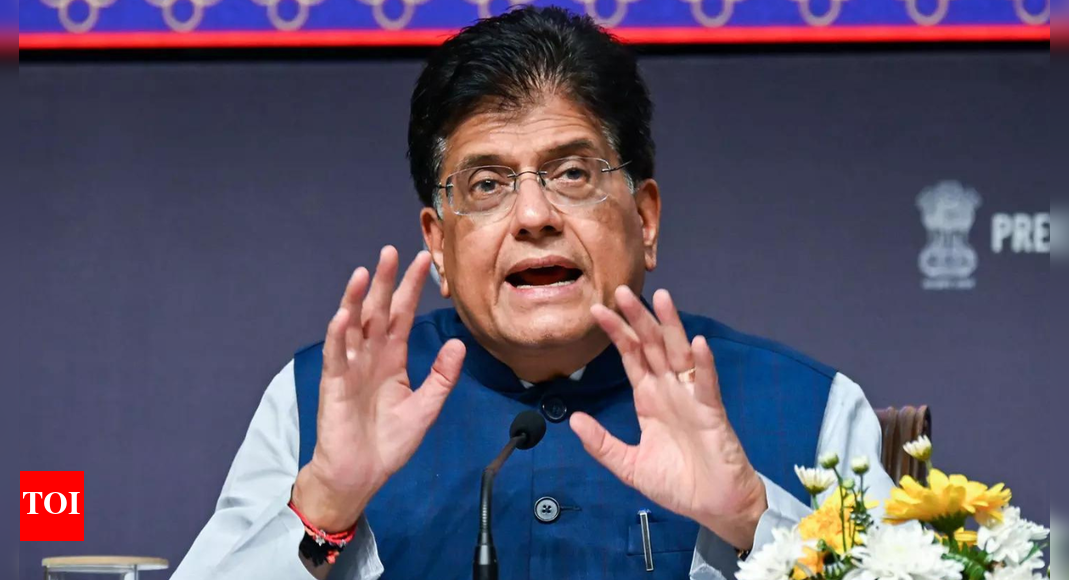

I speak as a videshi outsider, an Israeli researcher of India with many beloved Kashmiri and Bengali friends, but no family there or direct recollection of either tragedy in Kashmir or Bengal.

But then again, as an Israeli, a graduate of the Religious Zionist education system which currently contributes disproportionately to the IDF fighting force in Gaza and its casualty tally, and as a grandson to my grandfather and namesake Yeshaya Hanft who’s family and entire village were massacred by the Nazis, watching this epic film was a loaded experience in a different way. It offered many comparisons to take note of and reflect upon, from gratitude for the security offered to me by the State of Israel, to rage at predicament of my Bengali friends, to theological reflections from Jewish classical literature on the ways of creating meaning out of collective tragedy and grief to amass the strength to rise from them.

It is on these deeper themes that I wish to dwell on in this essay. I will recap various parts of the plot and assume that readers have already watched the film or intend to soon.

A Brief Recap

Shiva Pandit (Darshan Kumar) is a CBI officer sent to Kolkata to investigate the disappearance of a young woman. He is summarily notified that all evidence leads to Sardar Hussain (Saswata Chaterjee), an MLA from Murshidabad, but Sardar is so powerful, nobody will investigate him, and so, case closed. Shiva is indignant and refuses to comply.

His lead informant is a senile elderly woman, Bharati Banerjee (Pallavi Joshi) whom Gita had been living with. As the film progresses Maa Bharati begins to talk, and recalls not only recent events, but lengthy flashbacks from her youth. In these flashbacks the young Bharati (Simrat Kaur) is a revolutionary, who barely survives the carnage of Direct Action Day with the help of her guardian angel, a young Sikh warrior, Amar Singh (Eklavya Sood).

Together the power couple assist Gopal Patha (Sourav Das) in organizing Hindus for self-defense and retaliation, and subsequentially continue to be active in the struggle for impendence, revolutionary journalism, and the frantic scramble for self-defense amid the evermore threatening postures of the Miyar Fauj, a local Muslim mob led by the young Gholam Sarwar,(Namashi Chakraborty), Pir of Daira Sharif and self-styled Pakistani revolutionary and thug.

In this cinematic framework, the flashbacks from the chaotic violence of Partition are projected by Bharati’s flashbacks into the plot set in present-day West Bengal, in a grand repeat of Bengali history: the same perpetrators, same enablers, same victims, same crimes, the same desperate heroes and the same collective ineptitude. “But there will be communal riots!” was the excuse for not stopping Gholam long before he led his mob at Noakhali and remains the excuse for privileging his next incarnation, Sardar, over his hapless victims.

“Is Bengal the new Kashmir?” asks the refrain of the twice-tormented Kashmiri refugee, Shiva Pandit. This movie cries out for a negative answer.

Who are the Villains?

While watching this film it becomes obvious that there is another villain beyond the parallel characters of Gholam-Sardar: Gandhi.

From the first moment, Gandhi is portrayed as a holy fool. When approached nervously by young Bharti posing her deepest thoughts on the choice between violent and non-violent struggle, his response is that he must go now and milk the goat, and if she wants she can join. In the same symbolic scene Gandhi has a live snake carefully carried away without being harmed, caring for the viper more than for Bengal. When he empathically states that non-violence will lead to justice, Bharti asks what will happen if it does not lead to justice and is left unanswered.

In a later scene, Gandhi is laying on a bed fasting for the end of the Calcutta Killings and collecting weapons from Hindus who organized themselves for self-defense. When Gopal Partha arrives, he asks Gandhi what will happen if the Muslims attack again and rape our women. Gandhi replies that these women should commit suicide.

Gopal talks back: I will not surrender my weapon. If I was fighting with a needle or nail, I would not surrender them either. You ask me to choose between your ego and my dharma, and I choose dharma. At this point the audience in the theater burst out clapping.

Gopal has intuitively learned the first Zionist lesson from the Holocaust: There is nothing saintly in dying powerless. Do not march quietly like a lamb to the slaughter. Arm yourself, be vigilant and defend yourself, because no foreign army will do it for you. Self-defense, not passive sacrifice, is the price of freedom.

The Jewish Point of View: From the Classics to the Holocaust and back

Watching this film requires a knowledge of Indian history and politics that Jews and Westerners don’t usually possess. But if they did, any Jew versed in tradition watching this movie would have a few immediate cross-cultural references.

As a starting point, our prophets never promised us an easy life as God’s Chosen People. Quite the contrary to Gholam’s God who grants his ghazis booty and slaves as reward for their unmerited inherent superiority, in the Torah, privilege is inseparable from responsibility and accountability. To quote Amos (3;2): “You alone I have known intimately from all the families of the earth, therefore I will hold you to account for all your inequities”.

Therefore, Moses warns in the Torah in two lengthy chapters (Leviticus 26;14-46, Deuteronomy 28;15-68) of curses of the horrors that will befall Israel if they sin. Scenes like the one where a pack of buzzards descends to feast on the corpses in the streets of Kolkata are prophesied by Moses, and later in real time by Jeremiah on the streets of besieged Jerusalem: “And your carcasses will be fodder to all birds of the sky and earthly beasts, and there will no one to frighten them off” (Deuteronomy 28:26).

The shock of Oct. 7 – an ISIS-inspired invasion referenced in TBF by Muslim rioters arriving in Toyota-style pickup trucksat the home of the Hindu zamindar of Noakhali – was not because such unspeakable atrocities had never been committed upon us, but because we thought they could never happen in the independent state of Israel protected by the IDF. We were taught that Israel meant “Never Again”. But God works mysterious ways, that we have yet to comprehend.

Other Jews would default to Holocaust references. Young Bharti would reference to Hannah Szenes, the young Zionist resistance fighter sent as a paratrooper from British Mandatory Palestine to assist the Jews and Allies in Nazi-Occupied Hungary. Caught and tortured to death, her heroism is remembered by a poem she wrote before leaving for Europe. Set to a haunting tune by composer David Zehavi and sung on solemn occasions like Holocaust Remembrance Day, the poem written by an irreligious socialist Jew is a shrill prayer:

“My God, my God,

may it never end –

the sand and the sea,

the rustle of the water,

the lightning of the sky,

the prayer of man.”

Time and again, young Bharti is depicted in prayer to the Goddess or in her image: alight with the flames behind her, dagger in hand, waging war for her namesake, singing Vanda Mataram at moments of despair. “You are not allowed to die!” commands Amar, and Bharti remembers this for posterity.

The Biblical King David, poet and warrior, founder of our capital Jerusalem and of our only religiously legitimate royal dynasty, is the figure most associated with the Divine feminine in Jewish mysticism. In Psalms (118;16-18) he declares:

“God’s right hand is raised high! God right hand is waging war! I shall not die but I shall live and proclaim the works of God. God has ever tormented me but has not handed me over to death”.

Amar and Bharti conclude: “If there is an Ishwar, our sacrifice will not be in vain”.

Gandhi, King Saul and Amalek

But after these parallels, the stark differences cannot be missed. A starting point would be the question: Is there a Jewish Gandhi? We have a Biblical-inspired tradition justifying our collective powerlessness in exile from the Land of Israel as a punishment for our sins, but we do not have a substantial pacifist tradition. The end of all war is the most famous messianic vision (Isaiah ch. 11), but that was always a utopian vision, not a political program.

The closest figure I can reference is the biblical King Saul, our first king, coronated by the divine edict of prophet Samuel and later ousted by his edict for insubordination and replaced by King David and his line for eternity. The story of his insubordination (Samuel 1 chapter 15) is the most instructive biblical parallel to TBF, and it is worth recalling in full length.

King Saul was commanded to exterminate the nation/tribe of Amalek, the eternal and mortal enemy of Israel since the Exodus:

“Now go, attack Amalek, and proscribe all that belongs to him. Spare no one, but kill alike men and women, infants and sucklings, oxen and sheep, camels and donkeys!”

He amasses an army and attacks, but at the end of the battle he has mercy and spares King Agag and the cattle and returns with them alive. According to rabbinical tradition, that night Agag procreated and kept Amalek alive.

God comes to Samuel and notifies him:

“I regret that I made Saul king, for he has turned away from Me and has not carried out My commands.”

A few verses later come the following narrative (Samuel 1 15;12-33):

Early in the morning Samuel went to meet Saul… When Samuel came to Saul, Saul said to him, “Blessed are you to God! I have fulfilled God’s command.”

“Then what,” demanded Samuel, “is this bleating of sheep in my ears, and the lowing of oxen that I hear?”

Saul answered, “They were brought from the Amalekites, for the troops spared the choicest of the sheep and oxen for sacrificing to your God. And we proscribed the rest.”

Samuel said to Saul, “Stop! Let me tell you what God said to me last night!” “Speak,” he replied.

And Samuel said, “You may look small to yourself, but you are the head of the tribes of Israel. God anointed you king over Israel, and God sent you on a mission, saying, ‘Go and proscribe the sinful Amalekites; make war on them until you have exterminated them. Why did you disobey God and swoop down on the spoil in defiance of God’s will?”

Saul said to Samuel, “But I did obey God! I performed the mission on which God sent me: I captured King Agag of Amalek, and I proscribed Amalek, and the troops took from the spoil some sheep and oxen—the best of what had been proscribed—to sacrifice to your God at Gilgal.”

But Samuel said: “Does God delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices, as much as in obedience to God’s command? Surely, obedience is better than sacrifice, Compliance than the fat of rams. For rebellion is like the sin of divination, defiance, like the iniquity of oracle idols.

Because you rejected God’s command, [God] has rejected you as king.”

Saul said to Samuel, “I did wrong to transgress God’s command and your instructions; but I was afraid of the troops, and I yielded to them. Please, forgive my offense and come back with me, and I will bow low to God.”

But Samuel said to Saul, “I will not go back with you; for you have rejected God’s command, and God has rejected you as king over Israel.” As Samuel turned to leave, Saul seized the corner of his robe, and it tore.

And Samuel said to him, “God has this day torn the kingship over Israel away from you and has given it to another who is worthier than you. Moreover, the Eternity of Israel does not deceive or have a change of heart, for [God] is not human to have a change of heart.”

But [Saul] pleaded, “I did wrong. Please, honor me in the presence of the elders of my people and in the presence of Israel, and come back with me until I have bowed low to your God.” So Samuel followed Saul back, and Saul bowed low to God.

Samuel said, “Bring forward to me King Agag of Amalek.” Agag approached him with faltering steps; and Agag said, “Ah, bitter death is at hand!”

Samuel said: “As your sword has bereaved women, So shall your mother be bereaved among women.” And Samuel cut Agag down before God at Gilgal.

…

Saul is Gandhi. First merciful and weak, then sanctimonious and self-righteous, but in summary, as the prophet insists, adharmic. When dharma demands war, no puja, tapas, or bhajan can replace it. And the adharmic king must pay for his weakness with his throne.

The commandment to exterminate Amalek is decried in modern times for its cruelty: How can any nation be worthy of full extermination? How can children be guilty? How can property be incriminated?

While there is no realistic chance or aspiration by any faction in Israeli political life to kill every Gazan, the invoking of Amalek after Oct 7. by senior Israelis including PM Netanyahu could not have been more justified. A society in which all public voices openly applaud unspeakable acts fully in the realm of psychopathic fantasy, acts lauded by the mothers of the murderers and taught as holy gospel to small children, is unworthy of existence. The vast majority of Gazan houses were weaponized and boobytrapped (here is IDF Spox talking about this in 2014). Despite the Israeli government offering hefty reward and a free pass out of Gaza, not a single Gazan dissented enough to offer information leading to the Israeli hostages.

I’ll state it clearly: I don’t advocate for any war of annihilation nowadays. But I fully advocate for acknowledging danger and evil for what they are and what they mean, nothing more and nothing less, even if this means incriminating groups of millions of people right across our borders or even fellow citizens. Gholam and his men were a known threat from day one and dangerous men like them should be allowed no mercy or compassion and must be confronted with the full force of the law. As TBF points out, when Sardar is in power, there is no law. The price of refusing to apply genuine law and order is the disappearance of the ability to do so.

Theology and National Karma

At the most fundamental level, what allows Israel to rise from the ashes is Jewish theology carefully crafted from Biblical times around Jewish history: The basic unit in Judaism is the nation, with the individual and the universal being second and third thoughts appearing at later stages in our tradition.

Our nation has an eternal covenant with God, the “Eternity of Israel”, the master of unfolding history, who promised us the Holyland, Jerusalem and the return of rulers from the House of David. The Land of Israel is a living entity that spits out evildoers from its midst. If we sin, we are exiled, just as the evil Canaanites were decimated or the belligerent Palestinians received their Nakba. We have a theology to justify our demise by our own sins, and our rise and return to glory by our collective atonement and merit, guided by the very same Divine providence, love, zeal, and covenant.

Hindu Dharma is focused on the individual and then on the universal. The Indian nation plays no cosmic role as such, and Hindu intellectuals like Rajiv Malhotra takes the stance that history (and I will add politics, by extension of history to the present) has no divine significance and Hindus are liberated from its “tyranny of history-centrism” upon the Abrahamic theologies and mindset. There is the Ram Rajya, the dharmic kingdom led by the dharmic king, but there is no concept of “National Karma” that Judaism would apply to the nation of Israel.

With these guidelines, how can Hindus make sense of a collective tragedy after it has happened? Can they only wallow in shame and sorrow at the inexplicable collective ineptitude, cowardess, and blindness of the Bhadrloks, Kashmiris, Hindus, or the Indian government? If it is inexplicable, is it unpreventable? How can a nation rise from tragedy it can’t process productively and can’t fit into a healing narrative?

If one wants to uphold the alleged Hindu disregard for history, then what Hindus can agree on is the present. There is no excuse for dereliction of your duty to protect the nation and every individual from violence and abuse from now on.

But one wants to ascribe importance to learning lessons from history – and Hindu historians like Vikram Sampath prefer this path – then one must think hard about the lessons to learn. Learning the dangers of political Islam is one part, but the lesson can’t merely amount to knowing the depravity of your enemy. That would teach you nothing about your role in history and your agency to play it.

One common historical lesson is nonetheless shred by Hindus and Jews: The importance of unity. Hindus and Jews are both argumentative with a proclivity for infighting and creating internal fault lines. We can both agree upon our most famous historical lesson: United we stand, divided we fall.

This was reiterated so vividly by all our enemies commenting on the opportunity to attack that they saw presented by the aggressive protests led by old elites in opposition to the proposed judicial reforms of 2023. It would be no less fitting in the playbooks of ISI and their Woke Western academic allies attempting to exploit the fault lines of Indian society.

Whatever our political differences or fault lines are, we must never abandon our brethren. Never give up on “Bengalis”, “Diaspora” or any other group, and never attempt to sacrifice a political rival to save your own skin.

Your enemy does not care who believes in “Ganga Yamuna Tehzeeb” and who is a “Hindutva Extremist”, who is a Zionist, a “Settler” or a fully assimilated American Jew. In the end you are a target as a Hindu or Jew, with no other qualifier necessary. You can be as politically blind as the patriotic Jews of Weimar Germany or the loyalist gentry of colonial Kolkata, but as long as you as you are not actively siding with the enemy, you are on our side, like it or not. And in times of battle, our sovereign governments are divine messengers that will send the armed forces to kill and die for you, without asking your opinion. That is the way it should be in a dharmic kingdom.