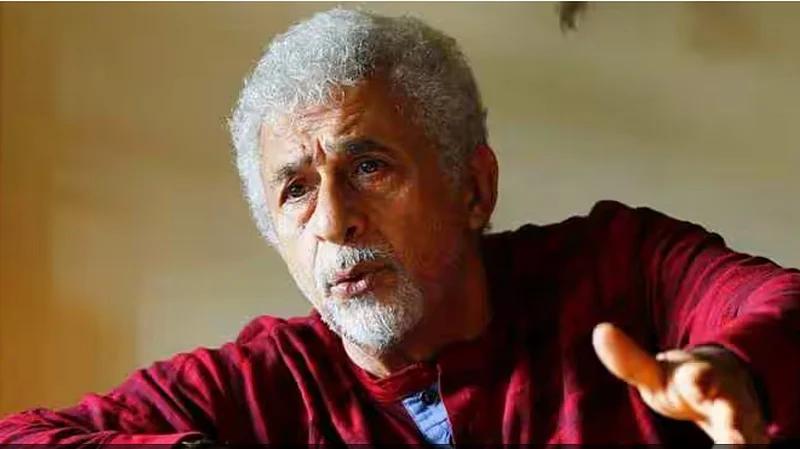

Naseeruddin Shah’s ‘disinvitation’ drama: How the actor turned an Urdu event snub into a political polemic

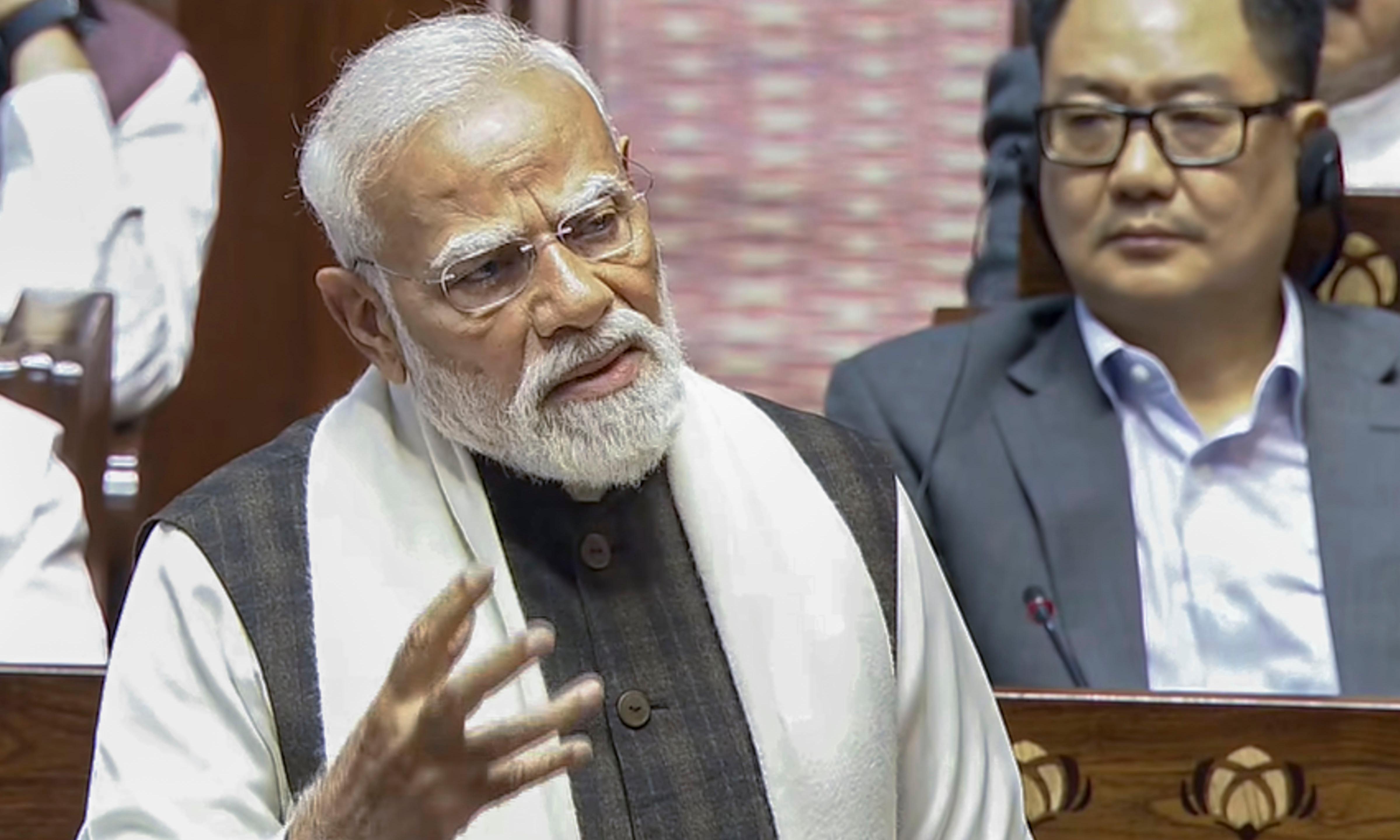

Naseeruddin Shah’s recent op-ed, published in the Indian Express, triggered by his alleged “disinvitation” from a Mumbai University Urdu Department event, is less a statement of fact and more a familiar performance of grievance politics. The actor claims he was first invited to Jashn-e-Urdu on February 1 and then informed a day before that his presence was no longer required. He further says no official explanation was offered and that the organisers publicly suggested he had declined the invitation himself, a claim he disputes. Up to this point, the matter is straightforward: an invitation was issued, later withdrawn, and the communication around that reversal was, at best, clumsy and opaque. That is the sum total of what is actually known. Everything else in Shah’s op-ed is inference, speculation, and political colouring. It is also hard to miss the irony: Shah is casting himself as a victim of “intolerance” for being disinvited from an event meant to commemorate Urdu, a language and literary tradition that has, for centuries, thrived in India’s plural cultural space. If anything, the very existence of such a university event undercuts the sweeping civilisational gloom he tries to paint. Yet he presents this episode not as an administrative lapse or institutional muddle, but as proof of a broader ideological crackdown. In his defence, Shah claims a very senior university official reportedly told him that he openly makes comments against India but such unverified random remarks cannot be taken as the University’s official stance to what Shah describes as ‘disinvitation’ for the Urdu event. Instead of seeking a formal clarification from the university or placing the correspondence in the public domain, Shah chose to leap straight to motive. He framed the episode as an act of ideological retaliation, attributing it to his “sharp political views” and to what he described as a climate of “rising intolerance.” In doing so, he converted an administrative or organisational decision, about which no confirmed reason is on record, into a morality play with himself cast as the silenced dissenter. This is precisely where Shah’s argument weakens. There is, at present, no public evidence establishing why the invitation was withdrawn. Universities cancel speakers for a host of reasons: scheduling conflicts, internal disagreements, funding issues, pressure from multiple sides, or simple bureaucratic dysfunction. None of these possibilities is flattering, but neither do they automatically amount to ideological censorship. By skipping the basic step of demanding a clear explanation and instead publishing an op-ed that imputes political motives, Shah replaces inquiry with insinuation. In his column, he goes further, rehearsing a familiar catalogue of complaints about the current political climate, the Prime Minister, “thought police,” “doublespeak,” and a country supposedly unrecognisable from the one he grew up in. None of this, however, establishes that Mumbai University disinvited him for these reasons. It merely uses the incident as a springboard to restate his long-standing political positions and to reinforce a narrative of personal and community victimhood. This pattern is not new. Shah has, for years, positioned himself as a cultural dissenter against what he sees as a majoritarian, nationalist turn in public life. He has repeatedly attacked films like The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story as propaganda and a “dangerous trend,” even invoking Nazi Germany to describe the popularity of such cinema. He has also blamed audiences for not supporting filmmakers he considers ideologically aligned with his own worldview. In other words, he is not a neutral commentator suddenly shocked by intolerance; he is an active participant in a deeply polarised cultural debate. That context matters because it explains why his op-ed reads less like a careful account of an administrative slight and more like a political manifesto built around a personal grievance. The episode becomes useful not as a question to be resolved but as a prop to reinforce a broader ideological narrative: that dissenting voices (of a particular kind) are being systematically squeezed out, and that Muslims and liberal critics are uniquely imperilled. The irony deepens when one recalls that Shah himself has, in the past, been dismissive of very real threats when they did not fit his preferred narrative. His comments downplaying the danger posed to Nupur Sharma by Islamist threats, later grotesquely contradicted by the Udaipur beheading of Kanhaiya Lal, stand as a stark reminder that his moral alarm system is highly selective. When violence or intimidation comes from quarters he is reluctant to confront, the threats become “hollow.” When he faces an unexplained professional setback, it is immediately elevated into proof of systemic persecution. None of this is to say that disinviting a speaker at the last minute without a clear expla

Naseeruddin Shah’s recent op-ed, published in the Indian Express, triggered by his alleged “disinvitation” from a Mumbai University Urdu Department event, is less a statement of fact and more a familiar performance of grievance politics. The actor claims he was first invited to Jashn-e-Urdu on February 1 and then informed a day before that his presence was no longer required. He further says no official explanation was offered and that the organisers publicly suggested he had declined the invitation himself, a claim he disputes.

Up to this point, the matter is straightforward: an invitation was issued, later withdrawn, and the communication around that reversal was, at best, clumsy and opaque. That is the sum total of what is actually known. Everything else in Shah’s op-ed is inference, speculation, and political colouring.

It is also hard to miss the irony: Shah is casting himself as a victim of “intolerance” for being disinvited from an event meant to commemorate Urdu, a language and literary tradition that has, for centuries, thrived in India’s plural cultural space. If anything, the very existence of such a university event undercuts the sweeping civilisational gloom he tries to paint. Yet he presents this episode not as an administrative lapse or institutional muddle, but as proof of a broader ideological crackdown.

In his defence, Shah claims a very senior university official reportedly told him that he openly makes comments against India but such unverified random remarks cannot be taken as the University’s official stance to what Shah describes as ‘disinvitation’ for the Urdu event.

Instead of seeking a formal clarification from the university or placing the correspondence in the public domain, Shah chose to leap straight to motive. He framed the episode as an act of ideological retaliation, attributing it to his “sharp political views” and to what he described as a climate of “rising intolerance.” In doing so, he converted an administrative or organisational decision, about which no confirmed reason is on record, into a morality play with himself cast as the silenced dissenter.

This is precisely where Shah’s argument weakens. There is, at present, no public evidence establishing why the invitation was withdrawn. Universities cancel speakers for a host of reasons: scheduling conflicts, internal disagreements, funding issues, pressure from multiple sides, or simple bureaucratic dysfunction. None of these possibilities is flattering, but neither do they automatically amount to ideological censorship. By skipping the basic step of demanding a clear explanation and instead publishing an op-ed that imputes political motives, Shah replaces inquiry with insinuation.

In his column, he goes further, rehearsing a familiar catalogue of complaints about the current political climate, the Prime Minister, “thought police,” “doublespeak,” and a country supposedly unrecognisable from the one he grew up in. None of this, however, establishes that Mumbai University disinvited him for these reasons. It merely uses the incident as a springboard to restate his long-standing political positions and to reinforce a narrative of personal and community victimhood.

This pattern is not new. Shah has, for years, positioned himself as a cultural dissenter against what he sees as a majoritarian, nationalist turn in public life. He has repeatedly attacked films like The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story as propaganda and a “dangerous trend,” even invoking Nazi Germany to describe the popularity of such cinema. He has also blamed audiences for not supporting filmmakers he considers ideologically aligned with his own worldview. In other words, he is not a neutral commentator suddenly shocked by intolerance; he is an active participant in a deeply polarised cultural debate.

That context matters because it explains why his op-ed reads less like a careful account of an administrative slight and more like a political manifesto built around a personal grievance. The episode becomes useful not as a question to be resolved but as a prop to reinforce a broader ideological narrative: that dissenting voices (of a particular kind) are being systematically squeezed out, and that Muslims and liberal critics are uniquely imperilled.

The irony deepens when one recalls that Shah himself has, in the past, been dismissive of very real threats when they did not fit his preferred narrative. His comments downplaying the danger posed to Nupur Sharma by Islamist threats, later grotesquely contradicted by the Udaipur beheading of Kanhaiya Lal, stand as a stark reminder that his moral alarm system is highly selective. When violence or intimidation comes from quarters he is reluctant to confront, the threats become “hollow.” When he faces an unexplained professional setback, it is immediately elevated into proof of systemic persecution.

None of this is to say that disinviting a speaker at the last minute without a clear explanation is acceptable. It isn’t. Institutions owe invitees transparency and basic professional courtesy. But there is a difference between demanding accountability and constructing a political narrative in the absence of evidence. Shah chose the latter.

If the actor genuinely wanted the truth, the obvious course was to seek a written explanation from the university and make that public. If the reason turned out to be political pressure or ideological vetting, the case would be far stronger and far more damaging to the institution involved. By pre-emptively assigning motive and publishing a polemic instead, Shah ensured that the episode would generate heat rather than light.

In the end, this controversy says less about Mumbai University, whose decision-making remains unexplained, and more about Shah’s reflex to interpret every personal slight through the lens of ideological victimhood. Conjecture is not evidence. And grievance, however eloquently written, is not a substitute for facts.