When 33 British MPs, including Jeremy Corbyn whom Rahul Gandhi met in 2022, campaigned for the killers of an Indian diplomat: The forgotten “Free Riaz and Qayyum” row

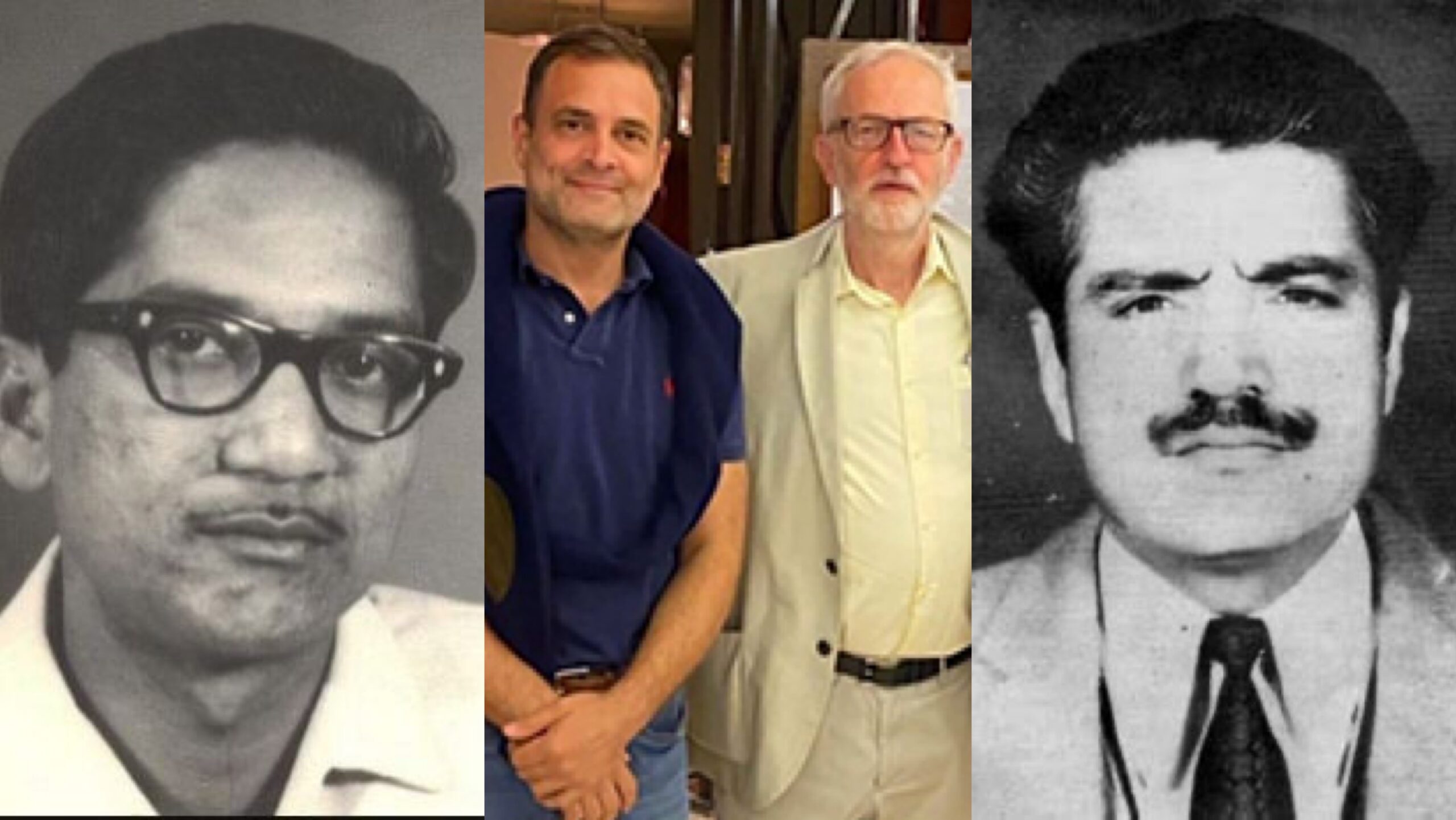

In an extraordinary and largely forgotten episode of British parliamentary history, official records reveal that as many as 33 Members of Parliament once rallied in support of two men convicted of kidnapping and murdering an Indian diplomat on British soil. The campaign, formalised through a parliamentary motion titled the “Free Riaz and Qayyum Campaign,” sought the early release of Mohammed Riaz and Abdul Quayyam Raja, both convicted for their role in the abduction and killing of Ravindra Mhatre, an Indian official posted in the United Kingdom. The episode exposes a troubling intersection of domestic British politics, diaspora activism, and international terrorism linked to the Kashmir conflict, raising uncomfortable questions about political sympathy for convicted militants and the selective framing of justice. The abduction that shook diplomacy The chain of events began on the evening of 3 February 1984 in Birmingham. Ravindra Mhatre, aged 48, served as an Assistant Commissioner at the Indian High Commission and was posted to the Indian Consulate in Birmingham. That evening, he was walking home from work carrying a birthday cake for his daughter when he was forcibly abducted outside his residence. Soon after, a militant outfit calling itself the “Kashmir Liberation Army” claimed responsibility. The group was later identified as a front for the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a separatist organisation advocating armed struggle against India. The kidnappers issued stark demands to the Indian government: a ransom of £1 million and the immediate release of Maqbool Bhat, the founder of the JKLF, who had been sentenced to death in India for terrorism-related offences, along with other imprisoned militants. For India, the situation represented an unprecedented diplomatic crisis. It was the first time an Indian diplomat had been kidnapped on foreign soil. The Indian government, however, refused to negotiate with terrorists. Murder and aftermath The standoff ended in tragedy. On 6 February 1984, three days after the abduction, Ravindra Mhatre’s body was discovered at a side street in a rural area southeast of Birmingham. He had been shot twice. The murder sent shockwaves through diplomatic and political circles in both India and the United Kingdom. In India, the killing hardened resolve. Just days later, on 11 February 1984, Maqbool Bhat was executed at Tihar Jail in New Delhi. The Indian government made it clear that hostage-taking and political murder would not influence its judicial or security decisions. British authorities, meanwhile, launched an intensive investigation. The probe led to the arrest of Mohammed Riaz and Abdul Quayyam Raja, both Pakistan nationals of Azad Kashmir origin. They were charged, tried, and convicted for their involvement in the kidnapping and murder. British courts sentenced both men to life imprisonment, recognising the gravity of the crime and its implications for diplomatic security. A Parliamentary campaign for convicted killers What followed a decade later remains startling even today. On 5 December 1994, Labour MP Max Madden tabled Early Day Motion (EDM) No. 12055 in the House of Commons. The motion was titled unequivocally: “FREE RIAZ AND QAYYUM CAMPAIGN.” The EDM called for the early release of Riaz and Raja and framed their continued incarceration as a political injustice rather than the lawful punishment of convicted murderers. In total, 33 MPs signed the motion, overwhelmingly from the Labour Party. Among the signatories were prominent and controversial figures such as Jeremy Corbyn, George Galloway, Ken Livingstone, Dennis Skinner, and Tony Banks. The language of the motion was striking. It argued that the two men were being “victimised for political reasons” and claimed that their treatment deviated from normal criminal justice standards. The signatories portrayed Riaz and Raja not as perpetrators of terrorism, but as casualties of geopolitical pressure and state overreach. The Corbyn connection and Rahul Gandhi’s 2022 meeting in the UK The controversy surrounding Jeremy Corbyn’s support for the “Free Riaz and Qayyum Campaign” acquires renewed significance in light of his meeting with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in 2022. During a visit to the United Kingdom, Rahul Gandhi attended events at Cambridge University purportedly to discuss India’s future after 75 years of independence. However, the trip drew sharp criticism after Gandhi was photographed meeting Corbyn, the former Labour Party leader widely regarded in India as openly hostile to Indian interests. Rahul Gandhi was accompanied by Indian Overseas Congress president Sam Pitroda during the meeting. The optics were particularly troubling given Corbyn’s well-documented history of supporting Kashmiri separatist narratives, echoing Pakistan’s position on Jammu and Kashmir, and endorsing calls for international intervention in India’s internal affairs. During

In an extraordinary and largely forgotten episode of British parliamentary history, official records reveal that as many as 33 Members of Parliament once rallied in support of two men convicted of kidnapping and murdering an Indian diplomat on British soil. The campaign, formalised through a parliamentary motion titled the “Free Riaz and Qayyum Campaign,” sought the early release of Mohammed Riaz and Abdul Quayyam Raja, both convicted for their role in the abduction and killing of Ravindra Mhatre, an Indian official posted in the United Kingdom.

The episode exposes a troubling intersection of domestic British politics, diaspora activism, and international terrorism linked to the Kashmir conflict, raising uncomfortable questions about political sympathy for convicted militants and the selective framing of justice.

The abduction that shook diplomacy

The chain of events began on the evening of 3 February 1984 in Birmingham. Ravindra Mhatre, aged 48, served as an Assistant Commissioner at the Indian High Commission and was posted to the Indian Consulate in Birmingham. That evening, he was walking home from work carrying a birthday cake for his daughter when he was forcibly abducted outside his residence.

Soon after, a militant outfit calling itself the “Kashmir Liberation Army” claimed responsibility. The group was later identified as a front for the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), a separatist organisation advocating armed struggle against India. The kidnappers issued stark demands to the Indian government: a ransom of £1 million and the immediate release of Maqbool Bhat, the founder of the JKLF, who had been sentenced to death in India for terrorism-related offences, along with other imprisoned militants.

For India, the situation represented an unprecedented diplomatic crisis. It was the first time an Indian diplomat had been kidnapped on foreign soil. The Indian government, however, refused to negotiate with terrorists.

Murder and aftermath

The standoff ended in tragedy. On 6 February 1984, three days after the abduction, Ravindra Mhatre’s body was discovered at a side street in a rural area southeast of Birmingham. He had been shot twice. The murder sent shockwaves through diplomatic and political circles in both India and the United Kingdom.

In India, the killing hardened resolve. Just days later, on 11 February 1984, Maqbool Bhat was executed at Tihar Jail in New Delhi. The Indian government made it clear that hostage-taking and political murder would not influence its judicial or security decisions.

British authorities, meanwhile, launched an intensive investigation. The probe led to the arrest of Mohammed Riaz and Abdul Quayyam Raja, both Pakistan nationals of Azad Kashmir origin. They were charged, tried, and convicted for their involvement in the kidnapping and murder. British courts sentenced both men to life imprisonment, recognising the gravity of the crime and its implications for diplomatic security.

A Parliamentary campaign for convicted killers

What followed a decade later remains startling even today. On 5 December 1994, Labour MP Max Madden tabled Early Day Motion (EDM) No. 12055 in the House of Commons. The motion was titled unequivocally: “FREE RIAZ AND QAYYUM CAMPAIGN.”

The EDM called for the early release of Riaz and Raja and framed their continued incarceration as a political injustice rather than the lawful punishment of convicted murderers. In total, 33 MPs signed the motion, overwhelmingly from the Labour Party. Among the signatories were prominent and controversial figures such as Jeremy Corbyn, George Galloway, Ken Livingstone, Dennis Skinner, and Tony Banks.

The language of the motion was striking. It argued that the two men were being “victimised for political reasons” and claimed that their treatment deviated from normal criminal justice standards. The signatories portrayed Riaz and Raja not as perpetrators of terrorism, but as casualties of geopolitical pressure and state overreach.

The Corbyn connection and Rahul Gandhi’s 2022 meeting in the UK

The controversy surrounding Jeremy Corbyn’s support for the “Free Riaz and Qayyum Campaign” acquires renewed significance in light of his meeting with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in 2022. During a visit to the United Kingdom, Rahul Gandhi attended events at Cambridge University purportedly to discuss India’s future after 75 years of independence. However, the trip drew sharp criticism after Gandhi was photographed meeting Corbyn, the former Labour Party leader widely regarded in India as openly hostile to Indian interests.

Rahul Gandhi was accompanied by Indian Overseas Congress president Sam Pitroda during the meeting. The optics were particularly troubling given Corbyn’s well-documented history of supporting Kashmiri separatist narratives, echoing Pakistan’s position on Jammu and Kashmir, and endorsing calls for international intervention in India’s internal affairs. During Corbyn’s tenure as Labour leader, the party passed resolutions calling for a UN-led referendum in Kashmir, an explicit challenge to India’s sovereignty. Corbyn himself had earlier held meetings with Congress-linked representatives to discuss Kashmir, an episode that triggered backlash in India and forced the Congress party into damage control.

Beyond India-related issues, Corbyn’s political career has been marred by repeated allegations of sympathy for extremist and terrorist organisations. He has previously referred to Hamas and Hezbollah as his “friends,” refused to unequivocally condemn IRA violence, and was associated with platforms that justified terrorist attacks in the UK itself. Under his leadership, the Labour Party was found by a UK human rights watchdog to have engaged in unlawful antisemitic harassment, ultimately leading to Corbyn’s suspension from the party he once led.

Against this backdrop, Rahul Gandhi’s engagement with Corbyn was seen by critics not as an innocuous overseas interaction, but as a tacit legitimisation of a figure whose political history includes defending convicted terrorists, endorsing separatism, and undermining India’s territorial integrity. For many in India, the meeting reinforced concerns about the Congress leadership’s willingness to associate with foreign politicians whose records are fundamentally at odds with India’s national and diplomatic interests.

Challenging the Judiciary and the Home Office

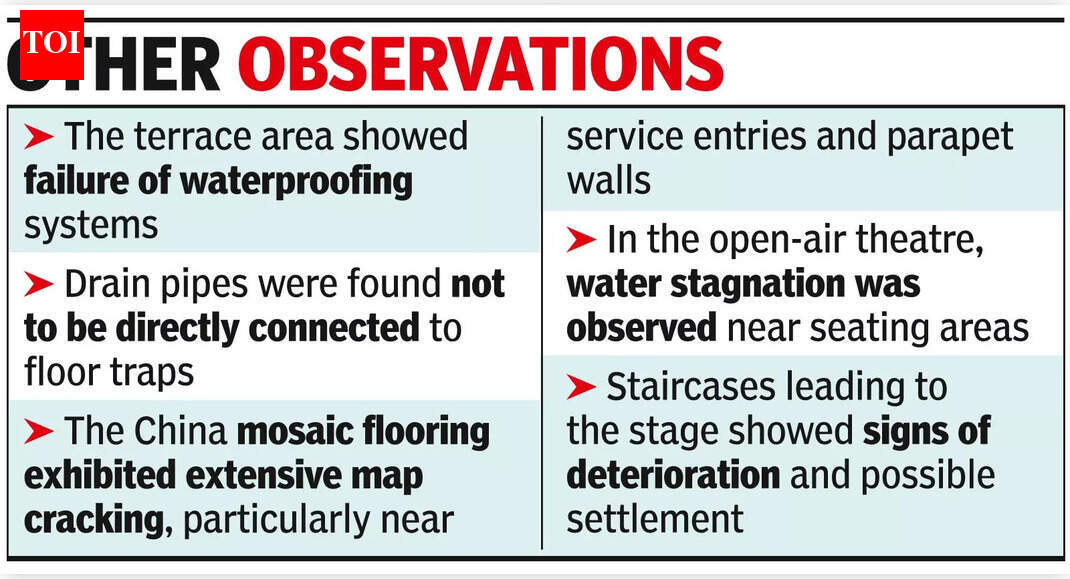

Central to the MPs’ argument was a dispute over sentencing tariffs, the minimum period a life-sentenced prisoner must serve before being considered for parole. According to the motion, the trial judge had originally recommended a minimum term of 10 years for Riaz and 15 years for Raja.

The EDM cited remarks attributed to the judge, including that Riaz was “unlucky to have been involved at all” and that there was “no hard, clear evidence against Raja.” These assertions formed the moral backbone of the campaign, suggesting that the convictions or sentences were excessive.

However, the MPs expressed particular outrage at the role of the Home Secretary. In 1988, the then-Home Secretary reportedly increased the tariffs to 20 years for Riaz and 25 years for Raja, effectively doubling the minimum time they would spend in prison. The motion condemned this move, alleging that the decision was made “secretly” and without transparency.

For the MPs involved, this was portrayed as an unacceptable politicisation of justice. They argued that politicians should not have the authority to override judicial recommendations and implied that diplomatic pressure, particularly India’s reaction to the murder, had influenced the harsher sentencing.

Street protests and political solidarity

The parliamentary motion did not exist in isolation. It openly endorsed activism on the streets. The EDM applauded supporters in Bradford and other cities who were organising protests and planning to picket outside the High Court on 8 December 1994, coinciding with a judicial review related to the case.

By publicly aligning themselves with these demonstrations, the MPs moved beyond abstract concern and into active political advocacy for the release of convicted terrorists. The motion explicitly called for the “early release of Riaz and Qayyum,” placing its signatories in direct opposition to the British judicial system’s verdict and the Indian government’s position.

For India, the campaign was deeply offensive. Ravindra Mhatre was a serving diplomat murdered in cold blood as part of a transnational terror plot. The attempt to recast his killers as victims of injustice highlighted a profound disconnect between British domestic politics and the lived reality of terrorism faced by Indian officials and civilians

A disturbing intersection of politics and terror

The “Free Riaz and Qayyum Campaign” remains a potent case study in how ideological activism, diaspora politics, and geopolitical conflicts can distort moral clarity. That elected MPs in a Western democracy publicly campaigned for the release of men convicted of murdering a foreign diplomat underscores the selective empathy often extended in cases involving Islamist or separatist violence.

The episode also foreshadowed broader debates that would later emerge around political responses to terrorism, especially when perpetrators are framed through lenses of “resistance” or “political struggle.”

More than four decades after Ravindra Mhatre’s murder, the parliamentary motion stands as a stark reminder: while victims of terrorism are often quickly forgotten, efforts to sanitise or excuse their killers can find enduring platforms, even within the halls of democratic power.