2025 in internal security: When India finally crushed Naxalism and cleansed the blot of Red Corridors from the landscape

When Amit Shah publicly set March 31, 2026, as the deadline to end Naxalism, it was not presented as an aspiration or political slogan. It was presented as a timeline. That distinction matters. Deadlines are announced only when the outcome is already visible on the ground, when the remaining task is closure, not conquest. The war against Naxalism is not a small chapter in India’s internal security. It is the longest-running internal armed conflict, spanning 5 decades, multiple governments, and vast forested regions once known as the Red Corridor. For years, the state tried to manage it by counter operations, negotiating pauses, and reducing casualties. If victory was discussed at all, it was done so with caution. That caution disappeared in 2025. This year was more than just increased encounters or routine operations. 2025 marked the decisive shift from managing Naxalism to dismantling it systematically and breaking its organisational, territorial, and ideological back. The movement lost its senior leadership, operational depth, recruitment capacity, and, most importantly, the confidence of its own cadres. Entire districts slipped out of Maoist hands. Hundreds surrendered. Safe zones collapsed. It would be an understatement to refer to this as “progress.” What India is witnessing is the endgame of an insurgency that once claimed to represent the oppressed and mainly survives by intimidation and force. The assertion that Naxalism is coming to an end is not political messaging. It is a conclusion derived from empirical data that, when considered collectively, go in a single direction. The final announcement may come in 2026. But the war, for all practical purposes, turned irreversible in 2025. Naxalism is done and dusted. Why 2025 changed everything India’s fight against Naxalism moved in cycles for decades. An offensive would follow a major ambush. Talks, a ceasefire, or a political pause would follow an offensive. The objective was containment, limiting casualties, protecting roads and polling booths, and preventing violence from spilling into cities. Naxalism was treated as a chronic condition, not a solvable one. That mindset quietly but decisively broke in 2025. What changed was not just intensity but intent. The state stopped treating Naxalism as an “area management” problem and began treating it as an organisation that had to be dismantled end to end. The focus shifted away from symbolic presence and towards sustained domination, not for days or weeks, but for months at a stretch. Forests that once functioned as Maoist sanctuaries were no longer entered episodically; they were occupied, mapped, and held. The rejection of ambiguity was equally important. There was no attempt to maintain the appearance of equal conflicting messages on ceasefires, and no parallel track of negotiations operating concurrently with operations. The security establishment’s message was clear that this stage is about completely denying space, not negotiating it. This clarity had cascading effects. Intelligence quality improved because local populations sensed permanence rather than temporary raids. Cadres began to realise that earlier escape routes no longer existed. Leadership found itself increasingly isolated from foot soldiers. The insurgency’s most significant historical advantage was time that stopped working in its favour. In earlier years, Naxalism survived by waiting out governments. In 2025, it ran into an immovable force that was no longer waiting, but kept hammering and crushing like a juggernaut. Operation Kagar and the new security doctrine If 2025 sees a change in intent, Operation Kagar will reflect how that intent should be implemented on the ground. This was neither a one-time event nor a headline-grabbing spectacle. It became shorthand for a new operating doctrine, sustained, intelligence-driven, and uncompromising. Operation Kagar focused on controlling the area for extended periods, rather than previous operations that invaded Maoist territory. It conducted confrontations and then departed. Security personnel remained deep within previously unreachable jungle areas. Communication lines were interfered with, arms stockpiles were found, movement corridors were blocked, and hideouts were destroyed. Maoists were routinely refused access to the forests, which were no longer used as makeshift battlegrounds. A crucial change was the target audience for the operations. Instead of chasing small armed squads after attacks, forces focused on eliminating area commanders, zonal leaders, and senior operatives who held the organisation together. Across Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and adjoining regions Maoist strength was never about numbers alone; it was about hierarchy and discipline. Once that spine began to crack, the movement started losing coherence. Coordination was equally important. Central forces, state police units, and elite jungle warfare teams worked in sync, sharing i

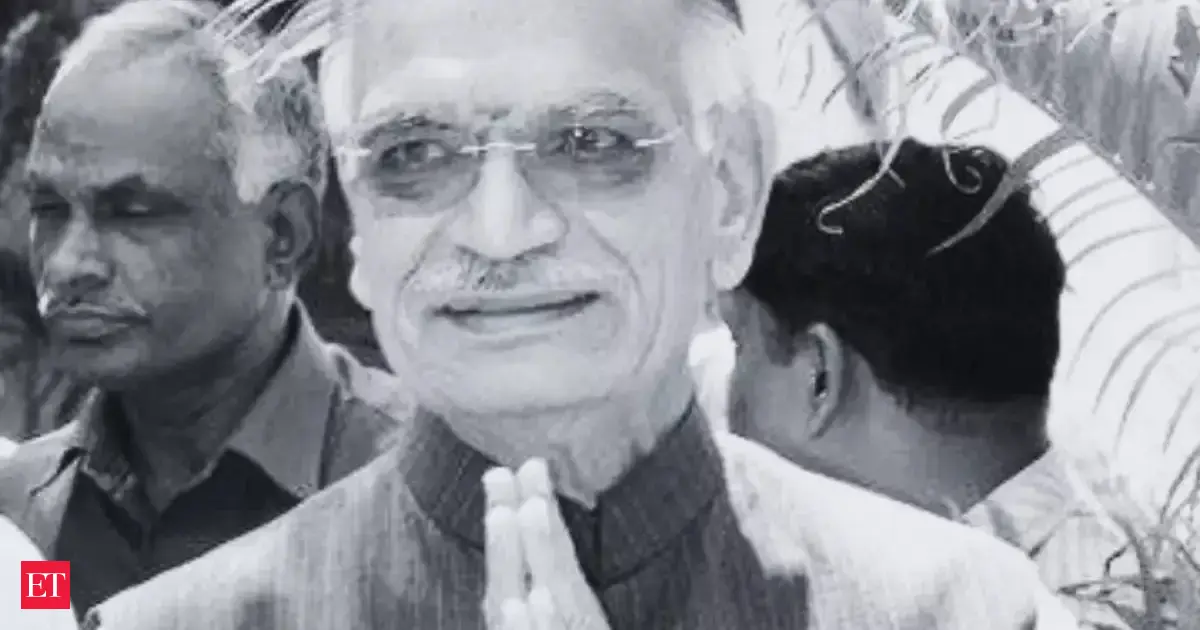

When Amit Shah publicly set March 31, 2026, as the deadline to end Naxalism, it was not presented as an aspiration or political slogan. It was presented as a timeline. That distinction matters. Deadlines are announced only when the outcome is already visible on the ground, when the remaining task is closure, not conquest.

The war against Naxalism is not a small chapter in India’s internal security. It is the longest-running internal armed conflict, spanning 5 decades, multiple governments, and vast forested regions once known as the Red Corridor. For years, the state tried to manage it by counter operations, negotiating pauses, and reducing casualties. If victory was discussed at all, it was done so with caution. That caution disappeared in 2025.

This year was more than just increased encounters or routine operations. 2025 marked the decisive shift from managing Naxalism to dismantling it systematically and breaking its organisational, territorial, and ideological back. The movement lost its senior leadership, operational depth, recruitment capacity, and, most importantly, the confidence of its own cadres. Entire districts slipped out of Maoist hands. Hundreds surrendered. Safe zones collapsed.

It would be an understatement to refer to this as “progress.” What India is witnessing is the endgame of an insurgency that once claimed to represent the oppressed and mainly survives by intimidation and force. The assertion that Naxalism is coming to an end is not political messaging. It is a conclusion derived from empirical data that, when considered collectively, go in a single direction. The final announcement may come in 2026. But the war, for all practical purposes, turned irreversible in 2025. Naxalism is done and dusted.

Why 2025 changed everything

India’s fight against Naxalism moved in cycles for decades. An offensive would follow a major ambush. Talks, a ceasefire, or a political pause would follow an offensive. The objective was containment, limiting casualties, protecting roads and polling booths, and preventing violence from spilling into cities. Naxalism was treated as a chronic condition, not a solvable one. That mindset quietly but decisively broke in 2025.

What changed was not just intensity but intent. The state stopped treating Naxalism as an “area management” problem and began treating it as an organisation that had to be dismantled end to end. The focus shifted away from symbolic presence and towards sustained domination, not for days or weeks, but for months at a stretch. Forests that once functioned as Maoist sanctuaries were no longer entered episodically; they were occupied, mapped, and held. The rejection of ambiguity was equally important. There was no attempt to maintain the appearance of equal conflicting messages on ceasefires, and no parallel track of negotiations operating concurrently with operations. The security establishment’s message was clear that this stage is about completely denying space, not negotiating it.

This clarity had cascading effects. Intelligence quality improved because local populations sensed permanence rather than temporary raids. Cadres began to realise that earlier escape routes no longer existed. Leadership found itself increasingly isolated from foot soldiers. The insurgency’s most significant historical advantage was time that stopped working in its favour.

In earlier years, Naxalism survived by waiting out governments.

In 2025, it ran into an immovable force that was no longer waiting, but kept hammering and crushing like a juggernaut.

Operation Kagar and the new security doctrine

If 2025 sees a change in intent, Operation Kagar will reflect how that intent should be implemented on the ground. This was neither a one-time event nor a headline-grabbing spectacle. It became shorthand for a new operating doctrine, sustained, intelligence-driven, and uncompromising. Operation Kagar focused on controlling the area for extended periods, rather than previous operations that invaded Maoist territory. It conducted confrontations and then departed. Security personnel remained deep within previously unreachable jungle areas. Communication lines were interfered with, arms stockpiles were found, movement corridors were blocked, and hideouts were destroyed. Maoists were routinely refused access to the forests, which were no longer used as makeshift battlegrounds.

A crucial change was the target audience for the operations. Instead of chasing small armed squads after attacks, forces focused on eliminating area commanders, zonal leaders, and senior operatives who held the organisation together. Across Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and adjoining regions Maoist strength was never about numbers alone; it was about hierarchy and discipline. Once that spine began to crack, the movement started losing coherence.

Coordination was equally important. Central forces, state police units, and elite jungle warfare teams worked in sync, sharing intelligence in real time. Operations no longer ended due to logistical constraints or political hesitation. Pressure was maintained until results were achieved. Operation Kagar symbolised this new reality that the state was no longer visiting Maoist territory. It was taking it back and staying there.

Leadership decapitation: Breaking the entire top command of the Maoists

What finally pushed Naxalism into a downward spiral was not just territorial loss but the systematic destruction of its leadership structure. For decades, the Maoist movement survived setbacks because its command chain remained intact. Foot soldiers could be replaced, but commanders could not. That equation flipped in 2025.

Sustained operations began eliminating area committee members, zonal commanders, and senior strategists who had operated with near impunity for years. These were not symbolic figures but operational brains, men who coordinated attacks, managed recruitment, handled finances, and maintained links between scattered units. Their removal did not just weaken the movement, but it paralysed it. It had an instant effect. As leadership was wiped out or was on the constant run, the local squads were left with no direction. Supply chains broke down. Intelligence leaks increased.

Cadres no longer knew whom to trust or where to regroup. In several regions, Maoist units disintegrated rather than fight.

Additionally, there was no credible second line ready to take charge. The old leadership had aged, and younger recruits lacked both ideological conviction and battlefield authority. What remained was a hollowed-out organisation with arms but leaderless.

By targeting the command rather than the crowd, the state achieved what decades of firefights could not. It broke the Maoists’ ability to function as a movement.

Surrenders by the hundreds, Govt’s message: Give up arms or die

Encounters show pressure, but surrenders reveal collapse. Furthermore, in 2025, the scale of Maoist surrenders spoke louder than firefights. Across Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and adjoining regions, hundreds of Naxal cadres laid down arms, including senior operatives and reward-carrying commanders who had spent years inside the movement.

These were not peripheral sympathisers. Many were trained fighters and organisers who understood the risks of defection. They surrendered not because of a single encounter, but because leadership had been wiped out, jungle sanctuaries were compromised, and escape routes no longer existed. Surrender became a credible exit. Rehabilitation policies and assurances of security made it clear that laying down arms was no longer a trap but a way out. When an insurgency is outgunned, it doesn’t end. When their own cadres start to fall, they come to an end.

When their own cadres no longer think the battle is worthwhile, they come to an end.

The ceasefire noise and why the government ignored It

As pressure began to build and the Maoist structure began to collapse, calls for a “ceasefire” suddenly grew louder. These appeals were amplified by left-leaning activists and sections of civil society that had long argued for talks. But this was not a peace initiative, but a pressure tactic from a weakening insurgency.

Ceasefires have historically allowed Maoist groups to regroup, rearm, and regain relevance. The government’s refusal to pause the operations shows confidence. Negotiations are tools of resolution, not rescue mechanisms for collapsing movements. By rejecting ceasefire demands, the state made its intent unmistakable: this phase was not about managing Naxalism’s decline, but it was about finishing it.

2026 will be the formal announcement, the war is over

In March 2026, when the government publicly declares an end to Naxalism, it will be an administrative milestone rather than the actual moment of victory. The decisive shift has already taken place. By 2025, the insurgency had lost its leadership, territorial depth, recruitment capacity, and ideological momentum. These are the four pillars that allow such movements to survive. What remains are scattered remnants, not a coherent force. The Red Corridor no longer exists as a continuous operational zone. Forests that once functioned as sanctuaries are under sustained security presence. The Maoist narrative of revolutionary inevitability has collapsed under the weight of its own irrelevance.

This does not mean the work ends with the silencing of guns. Post-conflict regions demand governance, development, and long-term political engagement. The vacuum left by violence must be filled by the state permanently and visibly to prevent relapse.

But one conclusion is now challenging to dispute: India is not witnessing the decline of Naxalism, but it is witnessing its closure. The announcement may come in 2026, but the end in every meaningful sense arrived in 2025.