Anti-Brahmin tirade, support for urban naxals, downplaying discrimination against general castes and more: Who is Disha Wadekar, the ‘hypocrite’ lawyer representing petitioners in UGC case

The Supreme Court of India stayed the implementation of the draconian University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations of 2026 on 29th January. However, outrage against the UGC guidelines and counter-narratives in support of it are keeping the debate alive and heated. In her desperation to justify the implementation of the caste-discrimination guidelines, advocate Disha Wadekar gave an absurd argument that if caste-based discrimination guidelines are made caste-neutral, then “What is the point of that provision of discrimination?” In an interview with The Telegraph India published on 2nd February, Disha Wadekar said, “Now everyone is pointing out that there is a separate definition of caste discrimination. Section 3(C) defines caste discrimination as caste-based discrimination, based on caste or race against Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBCs. Caste-based discrimination definition that everyone has a problem with, who should it include?” "Are you saying that SC, ST and OBCs, caste based discrimination should also include other categories? Then, what is the point of that provision of discrimination? Then there is no discrimination, right?"I mean, WHAT?!The Telegraph says Disha Wadekar here is a key figure… pic.twitter.com/yCOFfDZsZX— Sensei Kraken Zero (@YearOfTheKraken) February 4, 2026 “If that should be a caste-neutral definition is what the question is, then are you saying that alongside SC, ST, and OBCs, caste-based discrimination definition should also include other categories, and it should be caste neutral, then what is the point of that provision of discrimination then? Then there is no discrimination, right? That actually means that there is no discrimination,” she added. Disha Wadekar drew parallels between a caste-based discrimination definition and a gender-based discrimination definition and said, “It is like saying that gender-based discrimination definition should have men who say that I am being discriminated against on the basis of gender.” She inadvertently exposed her hypocrisy by making such a claim since the UGC Regulations of 2026 did not identify discrimination on the basis of gender exclusively for women. However, discrimination against the general castes has been specifically excluded. She further attempts to discredit the legitimate concerns raised by those protesting against the caste-based discrimination guidelines, saying that punishments will be civil remedies, and no one will be outrightly lodged in jail, and the committee will hear both sides before decidinga punishment proportionate to its findings in a matter. Outrageously flawed gender-discrimination analogy, presumed guilt and a deliberate overlooking of how the UGC caste-based discrimination definition only widens the societal divide Advocate Disha Wadekar compared the definition of caste-based discrimination in question to gender laws by saying that “It is like saying that the gender-based discrimination definition should have men, who say that I am being discriminated against on the basis of gender.” The comparison that ‘upper caste’ groups or the general category should not be included in the caste-based discrimination definition, just as men should not be included in any gender-based discrimination definition of protective laws, essentially kills even the possibility of the acknowledgement of the general category facing discrimination due to their ascriptive identity. Similarly, Wadekar’s argument implies that men can never be discriminated against based on their gender. While prevalence does shape opinions, and even policies and laws, it does not mean that the non-protected groups are immune to discrimination based on their caste or gender-based identity. Wadekar’s logic plays into the general notion that if caste-based discrimination has taken place somewhere, the victim must by default be from the SC, ST, or OBC category while the discriminator must be from the general category. It is like legitimising the coarse argument of presumed guilt, “Ye purush hai, isne toh kia hi hoga [discrimination/harassment]” and “Ye upper-caste wala hai, isne kia hi hoga caste-based discrimination]. However, there have been incidents, and there is an undeniable possibility of ‘upper-caste’ individuals being subjected to discrimination and harassment based on their caste identity. There have been incidents in the past where genocidal slogans have been raised on campus, calls for Brahmin exodus have been made, and other similar incidents have been reported. Interestingly, while Wadekar suggests that gender-based discrimination happens only against women and thus men should not be included in such definitions, the UGC rules on gender-based discrimination are gender-neutral. The UGC rules cover discrimination against all humans, be it women, men, or the third gender. Regulation 3(d) of the UGC (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal of

The Supreme Court of India stayed the implementation of the draconian University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations of 2026 on 29th January. However, outrage against the UGC guidelines and counter-narratives in support of it are keeping the debate alive and heated. In her desperation to justify the implementation of the caste-discrimination guidelines, advocate Disha Wadekar gave an absurd argument that if caste-based discrimination guidelines are made caste-neutral, then “What is the point of that provision of discrimination?”

In an interview with The Telegraph India published on 2nd February, Disha Wadekar said, “Now everyone is pointing out that there is a separate definition of caste discrimination. Section 3(C) defines caste discrimination as caste-based discrimination, based on caste or race against Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and OBCs. Caste-based discrimination definition that everyone has a problem with, who should it include?”

"Are you saying that SC, ST and OBCs, caste based discrimination should also include other categories? Then, what is the point of that provision of discrimination? Then there is no discrimination, right?"

— Sensei Kraken Zero (@YearOfTheKraken) February 4, 2026

I mean, WHAT?!

The Telegraph says Disha Wadekar here is a key figure… pic.twitter.com/yCOFfDZsZX

“If that should be a caste-neutral definition is what the question is, then are you saying that alongside SC, ST, and OBCs, caste-based discrimination definition should also include other categories, and it should be caste neutral, then what is the point of that provision of discrimination then? Then there is no discrimination, right? That actually means that there is no discrimination,” she added.

Disha Wadekar drew parallels between a caste-based discrimination definition and a gender-based discrimination definition and said, “It is like saying that gender-based discrimination definition should have men who say that I am being discriminated against on the basis of gender.”

She inadvertently exposed her hypocrisy by making such a claim since the UGC Regulations of 2026 did not identify discrimination on the basis of gender exclusively for women. However, discrimination against the general castes has been specifically excluded.

She further attempts to discredit the legitimate concerns raised by those protesting against the caste-based discrimination guidelines, saying that punishments will be civil remedies, and no one will be outrightly lodged in jail, and the committee will hear both sides before decidinga punishment proportionate to its findings in a matter.

Outrageously flawed gender-discrimination analogy, presumed guilt and a deliberate overlooking of how the UGC caste-based discrimination definition only widens the societal divide

Advocate Disha Wadekar compared the definition of caste-based discrimination in question to gender laws by saying that “It is like saying that the gender-based discrimination definition should have men, who say that I am being discriminated against on the basis of gender.”

The comparison that ‘upper caste’ groups or the general category should not be included in the caste-based discrimination definition, just as men should not be included in any gender-based discrimination definition of protective laws, essentially kills even the possibility of the acknowledgement of the general category facing discrimination due to their ascriptive identity. Similarly, Wadekar’s argument implies that men can never be discriminated against based on their gender.

While prevalence does shape opinions, and even policies and laws, it does not mean that the non-protected groups are immune to discrimination based on their caste or gender-based identity. Wadekar’s logic plays into the general notion that if caste-based discrimination has taken place somewhere, the victim must by default be from the SC, ST, or OBC category while the discriminator must be from the general category. It is like legitimising the coarse argument of presumed guilt, “Ye purush hai, isne toh kia hi hoga [discrimination/harassment]” and “Ye upper-caste wala hai, isne kia hi hoga caste-based discrimination].

However, there have been incidents, and there is an undeniable possibility of ‘upper-caste’ individuals being subjected to discrimination and harassment based on their caste identity. There have been incidents in the past where genocidal slogans have been raised on campus, calls for Brahmin exodus have been made, and other similar incidents have been reported.

Interestingly, while Wadekar suggests that gender-based discrimination happens only against women and thus men should not be included in such definitions, the UGC rules on gender-based discrimination are gender-neutral. The UGC rules cover discrimination against all humans, be it women, men, or the third gender.

Regulation 3(d) of the UGC (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal of Sexual Harassment of Women Employees and Students in Higher Educational Institutions) Regulations, 2015, and other related clauses explicitly require higher educational institutions (HEIs) to act on sexual harassment complaints from male, female, and third gender individuals. This gender-neutrality also extends to broader grievance mechanisms, including the UGC Redressal of Grievances of Students Regulations, 2023, which although keeps women in central focus, says, “Act decisively against all gender-based violence perpetrated against employees and students of all sexes recognising that primarily women employees and students and some male students and students of the third gender are vulnerable to many forms of sexual harassment and humiliation and exploitation”.

The UGC has to a great extent managed to make gender-based protections gender-neutral without losing their core purpose, which is to address the structural and more prevalent discrimination while still ensuring redress for men or transgender individuals in cases that occur.

If this logic can successfully be applied to gender-based discrimination, where despite the prevalence being overwhelmingly against the rules remain inclusive.

In another interview, Wadekar says that she does suggest that upper-caste students do not experience harassment or victimisation at all, but cases are “typically individual-specific and not rooted in ascriptive group identity.”

A simple question arises here: how did she arrive at the conclusion that cases of harassment or victimisation of upper-caste students are ‘typically individual-specific’, and not ‘rooted in ascriptive group identity’? Can or have not Brahmins or other upper caste individuals not targeted for their pure vegetarian food preferences, or their Shikha (tuft of hair) or for wearing Janeu (sacred thread) by those linking their harmless religious practice to caste supremacism?

Back in 2022, “Brahmin-Baniyas, we are coming for you. We will avenge”, “Go back to Shakha”, “Brahmins Leave the Campus”, “Brahmin Bharat Chhodo”, “Now there will be blood” and other such slogans were spray-painted on the walls of Delhi’s Jawaharlal University by leftist groups. The professors targeted by the miscreants included Nalin Kumar Mohapatra, Raj Yadav, Pravesh Kumar, and Vandana Mishra.

1) This is from JNU.

— Anshul Saxena (@AskAnshul) December 1, 2022

Slogans on the wall:

1. Brahmin Bharat Chhodo.

2. Brahmino-Baniyas, we are coming for you! We will avenge.

School of Language Literature and Culture Studies in JNU. (2nd building, 3rd floor). pic.twitter.com/h4lGkotana

In April 2022, “Kashmir to bas jhanki hai, poora Bharat baaki hai” (Kashmir is only the beginning, whole India is still there) and “Brahman Teri kabr khudegi BHU ki dharti par” (Graves of the Brahmins will be dug at the BHU campus), slogans were written inside Banaras Hindu University.

In 2024, Ashoka University students shouted anti-Brahmin-Baniya slurs during demonstrations on 26th March. Social media users shared videos of the students chanting “Brahmin-Baniyawaad Murdabad” and other similar provocative phrases. In addition to abusing the Baniya and Brahmin communities, they chanted “Jai Savitri-Jai Fatima” and “Jai Bheem-Jai Meem”, while also demanding on-campus caste census and reservation.

In Karnataka, there have been incidents wherein Brahmin students were asked to cut off their Janeu before appearing for the CET exam. In Shivamogga, a Brahmin student was forced to cut his Janeu, throw it in the dustbin and only then was he allowed to appear in the exam, even as there was no rule that Janeu or any such religious objects were banned. Not to forget, despite what the Dharma says, Janeu/Janivara/Poonool is often associated with Brahmins and is described by ‘left-liberal’ cabal as a symbol of Brahminism and Brahmin caste superiority. In fact, Tamil Nadu has a history of the Poonool of Brahmins being forcibly cut to mock them, and such incidents continue to occur.

These incidents indicate that the so-called upper-caste groups are also subjected to harassment or discrimination based on their ascriptive group identity. The ‘Brahmins Leave Bharat’ or ‘Graves of Brahmins will be dug’, or ‘avenge Baniyas’ slogans invoke genocidal and expulsion rhetoric rooted in supposed historical group roles, reflecting the structural discrimination Disha Wadekar attributes only to SC, ST and OBCs.

Not all incidents of victimisation of upper caste students are ‘individual-specific’, some are rooted in group-based animus, and not all incidents of victimisation of SC, ST, or OBC students are caste-based discrimination or harassment, but individual-specific. Yet, Wadekar chose to dismiss caste-based discrimination against upper-caste individuals in HEIs as non-ascriptive. The only difference is that while the reserved groups would have the framework under the currently stayed UGC 2026 rules to have their real, imaginary, alleged or exaggerated grievances heard and redressed, the upper caste groups do not have such a specific framework.

With caste-based discrimination getting narrowly defined as unfair treatment against SC/ST/OBS with emphasis on structural or ascriptive identity harm, the UGC gave stronger institutional teeth, preventive duties, and symbolic recognition to complaints from the reserved categories, while similar grievances of the ‘upper-caste’ students would fall under the general 2023 rules.

Wadekar’s argument that the uproar by the general category people over the lack of a redressal is invalid since the 2023 regulation has been incorporated in the UGC 2026 regulation, and they can file complaints. This would not essentially address caste-based discrimination, as she herself admitted. Basically, not only Disha Wadekar, but the UGC itself is legitimising the unfair idea that upper caste individuals can never face harassment or victimisation based on their caste identity even as casteist slurs are hurled against them, calls for their violent ouster and genocide are given, and can only face individual-specific verbal and/or violent attack or harassment.

Since the UGC 2026 guidelines do not symmetrically recognise caste-based discrimination against general category students as a specific category of harm, a one-way street is created wherein the ascriptive caste discrimination is presumed unidirectional, while bidirectional or individual caste-specific from general category individuals is relegated to less specialised and less deterrent mechanism. Is this not in violation of Article 14, since the framework here essentially treats similar harms differently based on caste origins, rooted in the misconception that upper-caste students cannot face real caste-based discrimination due to their supposed historical caste ‘privilege’? Is it not a case of presumed guilt wherein GCs are labelled as inherent ‘oppressors’? Is there an intention to keep the ‘upper caste’ individuals guilt-trapped in the oppressor-oppressed matrix?

In conversation with The Telegraph India, advocate Disha Wadekar further suggests that those protesting against the UGC 2026 guidelines are doing a hue and cry over a non-issue like the misuse of the rules. This argument came even as there is a massive example of the general misuse of the SC/ST Act against upper-caste people. She said that it is not like a reserved category student would file a complaint before varsity authorities accusing anyone from the general category, and the accused person would immediately be stuffed in jail. Rather, she says, due process will be followed and the accused student will have the opportunity to present his/her case and present evidence etc, and only if the Committee finds the allegation to be true that warnings, or fines, etc., would be imposed.

However, what if a reserved category student files a complaint alleging caste-based harassment/discrimination against a general category student, the university’s committee dismisses the complaint as frivolous and the reserved category student ends up accusing the committee members of bias and files a case against them under the SC/ST Act? This may sound far-fetched and alarmist but in times where an entire village of Brahmin residents has been booked under the SC/ST Act over a wage-related dispute in Bihar’s Darbhanga, even as many of the accused men reside in Delhi-Mumbai for work, anything is possible.

The origins of the UGC regulations on equity, notification of the guidelines and the Supreme Court intervention

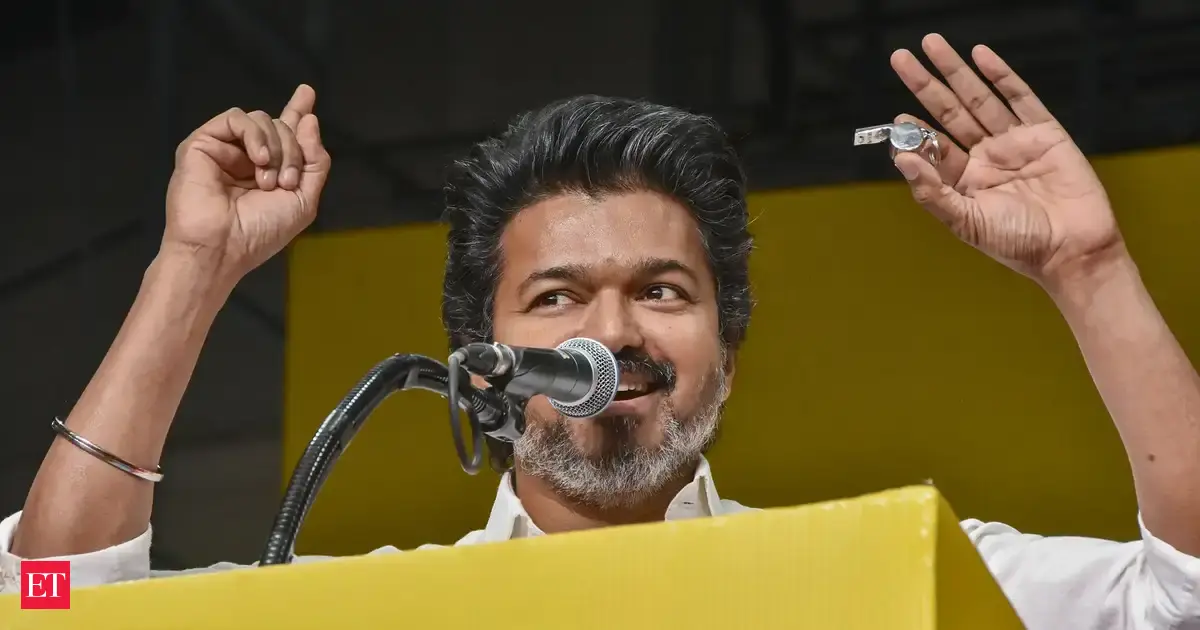

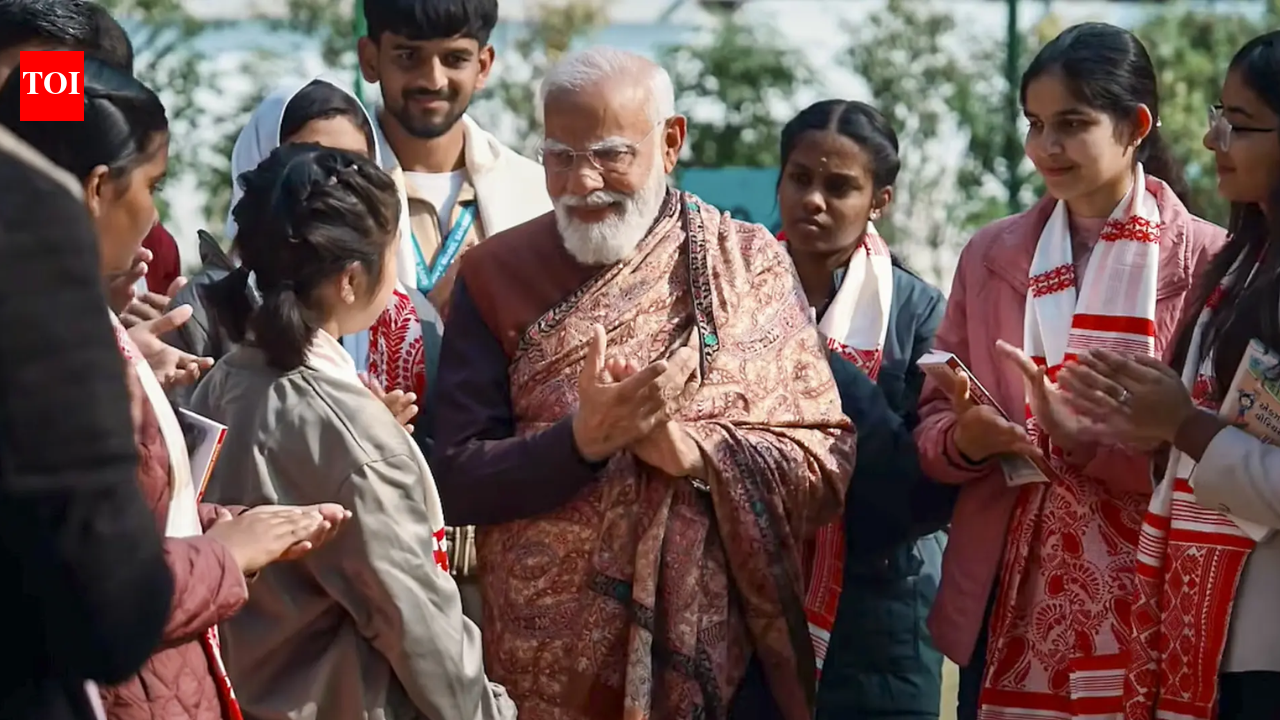

The 2025 draft regulations emerged out of a PIL filed in 2019 by mothers of students of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi, who died in 2016 and 2019, respectively. Their families alleged that the students committed suicide after being subjected to caste-based discrimination. The petitioner, represented by Senior Advocate Indira Jaising, along with advocates Prasanna S. and Disha Wadekar, sought the implementation of anti-discrimination measures in educational institutions. Wadekar drafted the 10 suggestions to be included in the UGC Bill, and most of those suggestions were accepted by the Central government. This came after the Supreme Court passed an order in September 2025, recording the ten specific suggestions made by the petitioners represented by Wadekar, Jaising and Prasanna S., and directed the UGC to revise the draft.

The PIL did not reportedly demand an entirely new set of regulations, but a strict enforcement of the existing University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Educational Institutions) Regulations, 2012. The 2012 rules required universities to establish Equal Opportunity Cells to handle complaints of discrimination, particularly against Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) students.

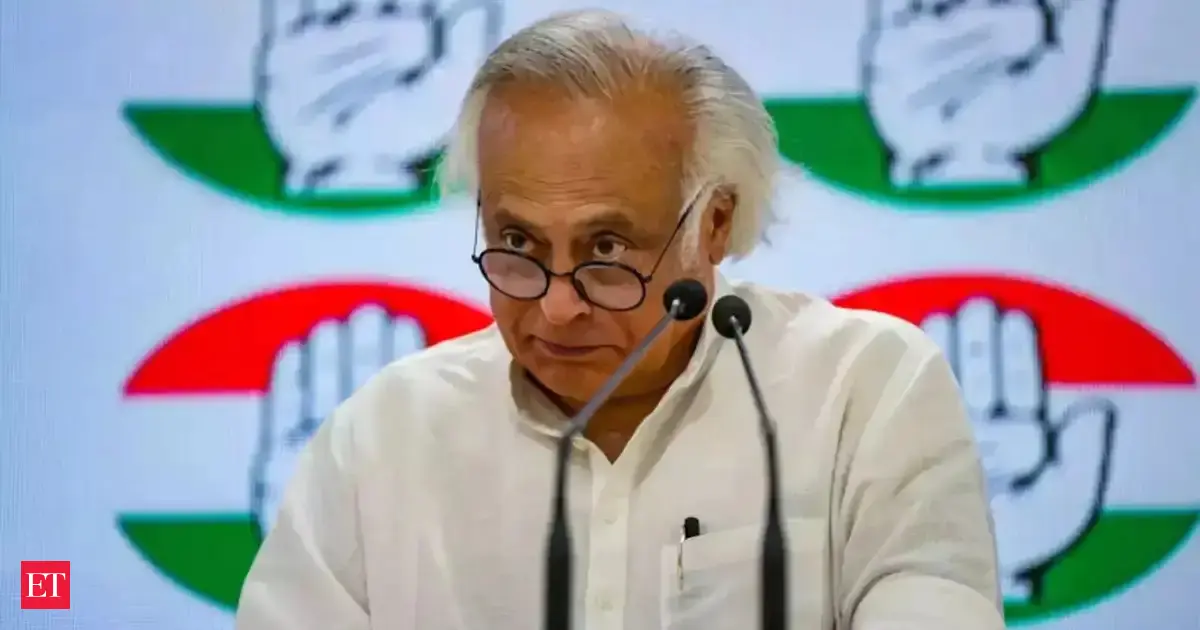

However, the petitioners were not happy with the 2025 draft regulations, and Senior Advocate Indira Jaising proposed ten core changes in the draft. The proposed reforms included grievance committees with substantial marginalised representation and grant withdrawal for non-compliance. The Supreme Court fixed an 8-week deadline for the finalisation of the regulations. Finally, the Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, 2026, were notified on January 13, 2026.

The 2026 regulations ruled out the general castes as victims of caste-based violence by restricting the category of victims to SCs, STs, and OBCs. There is no provision for general category students to raise a complaint when subjected to caste-based discrimination. The 2026 regulations not only assume that caste-based discrimination is only directed towards people from the SC, ST, and OBC communities, but, in a way, promote reverse caste-based discrimination by excluding general castes, which form a large section of the academic community, from protection.

As outrage erupted over the draconian rules, the matter reached the Supreme Court, which put a stay on the implementation of the UGC 2026 guidelines.

While a final decision in the matter is pending, the outrage around the UGC 2026 guidelines in the context of caste-based discrimination is justified not only because of its inherent flaw but also because this matter will set a precedent. It must not be forgotten how the suicide of Rohith Vemula was politicised, used by anti-Hindu elements to villainise ‘upper caste’ groups, and Karnataka Congress is coming up with caste-discrimination laws in Rohith Vemula’s name, while the closure report filed by Telangana Police states that Rohith Vemula did not even belong to the Scheduled Caste (SC) category. He was just using an SC certificate. The police concluded that he killed himself, fearing the exposure of his true caste identity.

In fact, advocate Disha Wadekar calls the day Rohith Vemula committed suicide “Shahadat Day”, suggesting that he was a ‘martyr’.

Disha Wadekar and her past shenanigans

Disha Wadekar is a Supreme Court lawyer with specialisation in personal law, caste discrimination, and anti-discrimination jurisprudence. She obtained her law degree from Columbia Law School in the US and is a co-founder of the Centre for Equity, Diversity and Equality (CEDE).

Unsurprisingly, Wadekar harbours deep disdain for the Brahmin community, as evident from her social posts. In one such post, she wrote, “Satyashodhak Jotiba Phule’s rationality and logic could make the Brahmin’s onions cry!”

In a post insinuating that Hinduism, the faith of the majority community of India, is oppressive, Wadekar wrote, “Not many know this- 51 years after Babasaheb’s revolutionary embrace of Buddhism, in May 2007, close to 25 thousand Nomadic and Denotified Tribals embraced Buddhism by reciting the 22 vows at Mumbai’s Mahalakshmi Racecourse. My family was amongst the many Pardhi, Kaikadi, Dombari… Mariaaiwale, Gondhali, Kadaklakshmiwale, Vasudev, Dawri Gosavi, Madari, Aswalwale, Waghri families who decided to break free from the shackles of Hinduism.”

Disha Wadekar is also a fan of urban naxal GN Saibaba, who was sentenced to life imprisonment by a Gadchiroli sessions court in 2017 for waging war against India for his Maoist links and involvement in anti-national activities. He was convicted under sections 13, 18, 20, 38 and 39 of the UAPA. G N Saibaba was first arrested in May 2014 on charges of being a member of the banned CPI-Maoists, plus providing logistics and carrying out recruitment for them.

Wadekar has earlier tried to bring in her ‘caste’ narrative even in the martyrdom of the soldiers of the Indian Army, and highlighted an article in the Caravan magazine on the “caste composition of the foot soldiers who die at the front”.

It must be recalled that the CRPF had strongly criticised the disgraceful caste-composition analysis of the martyrs of the 2019 Pulwama Islamic terror attack. CRPF chief Moses Dhinakaran had said that Jawans of the army are only “Indians” and that any caste, colour, and religion divide is non-existent in the Army.

She drafted the 10 specific suggestions to be put in the UGC bill. (Most were accepted by the BJP Gov).

— Scion of Mewar (@BromActivist) February 4, 2026

Btw! You can see her arguing here against the EWS.

Look at the contempt in her voice even for our poor brethren!

This is nothing but apartheid against GCs in motion. https://t.co/EY1rZCJMbR pic.twitter.com/Ta0OjhMMpp

Notably, Disha Wadekar is also opposed to the reservation given to the Economically Weaker Section (EWS) group, arguing that it is nothing but an “upper caste reservation”.