Mamata govt’s war against private industry: Bengal govt removes all incentives given, to save money for ‘welfare schemes’ job creators move HC

Several of India’s biggest industrial houses have approached the Calcutta High Court to challenge the West Bengal government’s controversial move to revoke all industry incentives granted since 1993. Companies including UltraTech Cement, Electrosteel Casting, Grasim Industries, Nuvoco Vistas and Dalmia Cement have filed petitions in the court in which they called the government’s legislation “unconstitutional”. The High Court has fixed 7th November as the date for a combined hearing of the appeals. Notably, in March 2025, the Mamata Banerjee-led government in West Bengal passed The Revocation of West Bengal Incentive Schemes and Obligations in the Nature of Grants and Incentives Bill, 2025, which was notified in April. The bill retrospectively withdraws all benefits provided under industrial policies since 1993. Subsidies on land, tax refunds, electricity, interest repayments, and other state-supported measures have been scrapped. The government justified the move by arguing that funds should be diverted towards “socio-economically disadvantaged and marginalised” groups. In its petition, Electrosteel Casting sought a declaration that the Act is “ultra vires and unconstitutional and the provisions contained therein are null and void and of no effect.” Industry department officials admitted that several companies complained they could no longer operate profitably after the announcement, but the government only promised that a “new industrial policy” was being drafted. A familiar story – Bengal’s hostility to industry This clash between the West Bengal government and industry is not an isolated development. For decades, industries operating in the state have seen a similar pattern that has dismantled the base for industrial growth. From the Left Front era that drove out major business houses with militant trade unionism and anti-capital rhetoric, to Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress government that rode to power on the back of anti-land acquisition movements in Singur and Nandigram, the state’s ruling establishments have consistently prioritised populism and ideological appeasement over industrial growth. In July 2025, the Union Government of India revealed that over 6,600 companies have left West Bengal since 2011, when Banerjee came to power. Over 2,200 departed in just the last five years. Many of these companies have shifted their base to Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Delhi. In 2024, Britannia shut down its decades-old factory in Kolkata. Earlier, Tata was driven out of Singur. Jute mills in the state continue to collapse. The politics of welfare over growth For the Mamata Banerjee-led government, the withdrawal of incentives is not about economics but about politics. Assembly elections are scheduled for 2026 and welfare subsidies are at the centre of her strategy. Critics, however, have argued that such policies condemn Bengal to stagnation. While other states lure investors with land at nominal prices and pro-business policies, Bengal keeps driving them out. The state’s share in India’s industrial output has slipped from over 10% to around 3.5% since the 1960s. West Bengal was once known as the “Manchester of the East”. However, now the state exports labour instead of goods. Lakhs of youth have been forced to migrate to Delhi, Kerala, or Maharashtra for survival. From industrial hub to socialist swamp The trajectory is unmistakable. The Left destroyed the industrial culture of West Bengal with their hostility to private enterprise. Then, after them, Banerjee finished the job with her politics of “Ma-Mati-Manush” that translated into mob resistance to factories and appeasement of vote banks. Today, the state is reduced to a dilapidated, poverty-stricken swamp of socialism, where mafias control contracts, infiltrators are courted, and genuine investors are shunned. The petitions filed by the industry giants in the High Court are not just about incentives. It is about whether West Bengal still has a future as a destination for investment. For the people of Bengal, this should be a reminder that their once-proud industrial heartland continues to be sacrificed at the altar of political populism.

Several of India’s biggest industrial houses have approached the Calcutta High Court to challenge the West Bengal government’s controversial move to revoke all industry incentives granted since 1993. Companies including UltraTech Cement, Electrosteel Casting, Grasim Industries, Nuvoco Vistas and Dalmia Cement have filed petitions in the court in which they called the government’s legislation “unconstitutional”. The High Court has fixed 7th November as the date for a combined hearing of the appeals.

Notably, in March 2025, the Mamata Banerjee-led government in West Bengal passed The Revocation of West Bengal Incentive Schemes and Obligations in the Nature of Grants and Incentives Bill, 2025, which was notified in April. The bill retrospectively withdraws all benefits provided under industrial policies since 1993. Subsidies on land, tax refunds, electricity, interest repayments, and other state-supported measures have been scrapped. The government justified the move by arguing that funds should be diverted towards “socio-economically disadvantaged and marginalised” groups.

In its petition, Electrosteel Casting sought a declaration that the Act is “ultra vires and unconstitutional and the provisions contained therein are null and void and of no effect.” Industry department officials admitted that several companies complained they could no longer operate profitably after the announcement, but the government only promised that a “new industrial policy” was being drafted.

A familiar story – Bengal’s hostility to industry

This clash between the West Bengal government and industry is not an isolated development. For decades, industries operating in the state have seen a similar pattern that has dismantled the base for industrial growth. From the Left Front era that drove out major business houses with militant trade unionism and anti-capital rhetoric, to Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress government that rode to power on the back of anti-land acquisition movements in Singur and Nandigram, the state’s ruling establishments have consistently prioritised populism and ideological appeasement over industrial growth.

In July 2025, the Union Government of India revealed that over 6,600 companies have left West Bengal since 2011, when Banerjee came to power. Over 2,200 departed in just the last five years. Many of these companies have shifted their base to Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Delhi. In 2024, Britannia shut down its decades-old factory in Kolkata. Earlier, Tata was driven out of Singur. Jute mills in the state continue to collapse.

The politics of welfare over growth

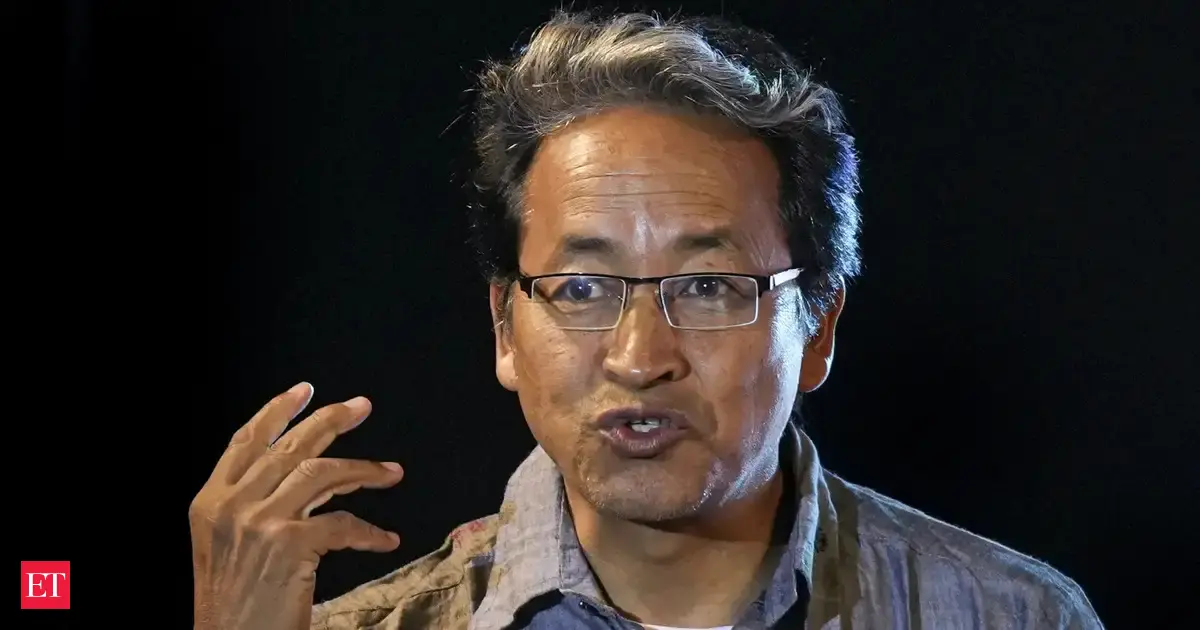

For the Mamata Banerjee-led government, the withdrawal of incentives is not about economics but about politics. Assembly elections are scheduled for 2026 and welfare subsidies are at the centre of her strategy.

Critics, however, have argued that such policies condemn Bengal to stagnation. While other states lure investors with land at nominal prices and pro-business policies, Bengal keeps driving them out. The state’s share in India’s industrial output has slipped from over 10% to around 3.5% since the 1960s. West Bengal was once known as the “Manchester of the East”. However, now the state exports labour instead of goods. Lakhs of youth have been forced to migrate to Delhi, Kerala, or Maharashtra for survival.

From industrial hub to socialist swamp

The trajectory is unmistakable. The Left destroyed the industrial culture of West Bengal with their hostility to private enterprise. Then, after them, Banerjee finished the job with her politics of “Ma-Mati-Manush” that translated into mob resistance to factories and appeasement of vote banks. Today, the state is reduced to a dilapidated, poverty-stricken swamp of socialism, where mafias control contracts, infiltrators are courted, and genuine investors are shunned.

The petitions filed by the industry giants in the High Court are not just about incentives. It is about whether West Bengal still has a future as a destination for investment. For the people of Bengal, this should be a reminder that their once-proud industrial heartland continues to be sacrificed at the altar of political populism.