SC rules, ‘Reserved category candidates scoring above the general cut-off can’t be denied open seats’: Read what it means, and how it is not about ‘double benefit’

In an important judgment that settles a long-running debate around merit and reservation, the Supreme Court has clearly stated that candidates belonging to SC, ST or OBC categories cannot be pushed out of the General (Open) category because of their caste, if they score higher than the general cut-off on merit. The court also added an important condition that reserved category candidates can be considered in the General category only if they have not taken any special benefits meant for reservation, such as age relaxation, extra attempts or other concessions. Bench rejects Rajasthan High Court administration’s appeal The ruling was delivered by a bench of Justices Dipankar Datta and Augustine George Masih, which dismissed the appeal filed by the Rajasthan High Court administration. The bench upheld the earlier decision of the Rajasthan High Court, which had ruled in favour of candidates who were denied a chance to move ahead in the recruitment process despite scoring well. The Supreme Court underlined that the General (Open) category does not belong to any particular caste or community. It exists for all candidates who qualify on merit, regardless of their social background. Background of the recruitment dispute The case is related to a large recruitment drive launched by the Rajasthan High Court in August 2022. The recruitment was carried out under the Rajasthan High Court Staff Service Rules, 2002 and the Rajasthan District Courts Ministerial Establishment Rules, 1986. Through this process, 2,756 posts were to be filled, including Junior Judicial Assistants and Clerks Grade-II, across the Rajasthan High Court, district courts and institutions like the Judicial Academy. The selection process had two stages. First was a written examination of 300 marks. The second stage was a computer-based typing test of 100 marks. As per the rules, candidates who scored above the minimum qualifying marks in the written exam were shortlisted for the typing test. The number of shortlisted candidates was limited to five times the number of vacancies in each category. Final selection was to be based on the combined score of both stages. The results of the written examination were declared in May 2023. This is where the controversy started. When category-wise shortlists were prepared for the typing test, it was found that the general category cut-off was around 196 marks. But the cut-offs for several reserved categories, such as Scheduled Castes, Other Backwards Classes, Most Backwards Classes and Economically Weaker Sections, were much higher. In some categories, the cut-off crossed even 230 marks. As a result, several candidates from reserved categories who had scored more than the General category cut-off were not shortlisted for the typing test. They failed to meet the much higher cut-off fixed for their own category. At the same time, General category candidates with lower scores were allowed to appear for the typing test. This led to serious grievances. The affected candidates argued that they were being unfairly blocked from the recruitment process despite having better marks than many others who were allowed to move ahead. Challenge before the Rajasthan High Court These candidates approached the Rajasthan High Court, arguing that the shortlisting method treated the General (Open) category as if it were meant only for unreserved candidates. They said this violated their right to equality and equal opportunity under Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. The High Court examined the issue in detail and agreed with the candidates. It held that while category-wise shortlisting is not illegal by itself, the stage at which it is applied and the way it is done are extremely important. The court ruled that if a reserved category candidate scores above the general cut-off without using any relaxation or concession, then that candidate must be considered in the General (Open) category at that level. Denying such candidates a chance was found to be unconstitutional. High Court orders fresh merit list The Rajasthan High Court ordered that the entire merit list be reworked. It directed the authorities to first prepare the General (Open) category list on merit. This list must include reserved category candidates who scored above the general cut-off, provided they had not taken any reservation-related benefits, the court said. The court also ordered that candidates who were excluded from the typing test be given an opportunity to appear in it. The High Court clarified that it was not abolishing reservation, nor was it saying that category-based shortlisting is always wrong. The problem lay in using caste labels too early in the selection process in a way that harmed meritorious candidates. Questions raised before the Supreme Court Unhappy with this decision, the Rajasthan High Court administration moved the Supreme Court. It argued that the adjustment of reserved categ

In an important judgment that settles a long-running debate around merit and reservation, the Supreme Court has clearly stated that candidates belonging to SC, ST or OBC categories cannot be pushed out of the General (Open) category because of their caste, if they score higher than the general cut-off on merit.

The court also added an important condition that reserved category candidates can be considered in the General category only if they have not taken any special benefits meant for reservation, such as age relaxation, extra attempts or other concessions.

Bench rejects Rajasthan High Court administration’s appeal

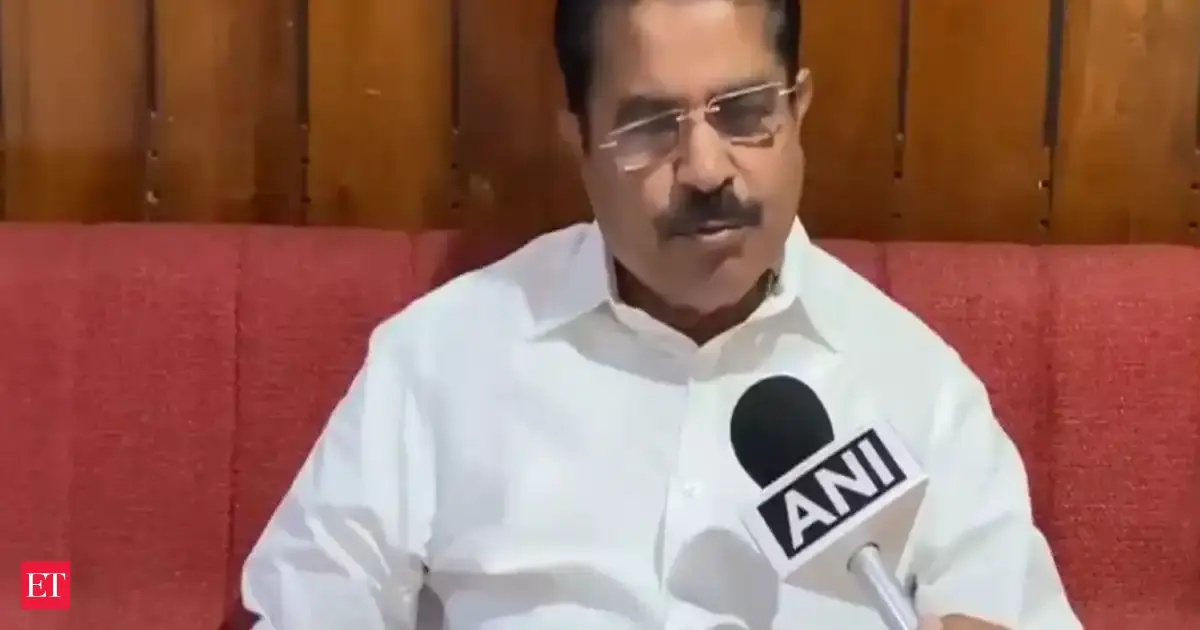

The ruling was delivered by a bench of Justices Dipankar Datta and Augustine George Masih, which dismissed the appeal filed by the Rajasthan High Court administration. The bench upheld the earlier decision of the Rajasthan High Court, which had ruled in favour of candidates who were denied a chance to move ahead in the recruitment process despite scoring well.

The Supreme Court underlined that the General (Open) category does not belong to any particular caste or community. It exists for all candidates who qualify on merit, regardless of their social background.

Background of the recruitment dispute

The case is related to a large recruitment drive launched by the Rajasthan High Court in August 2022. The recruitment was carried out under the Rajasthan High Court Staff Service Rules, 2002 and the Rajasthan District Courts Ministerial Establishment Rules, 1986. Through this process, 2,756 posts were to be filled, including Junior Judicial Assistants and Clerks Grade-II, across the Rajasthan High Court, district courts and institutions like the Judicial Academy.

The selection process had two stages. First was a written examination of 300 marks. The second stage was a computer-based typing test of 100 marks. As per the rules, candidates who scored above the minimum qualifying marks in the written exam were shortlisted for the typing test. The number of shortlisted candidates was limited to five times the number of vacancies in each category. Final selection was to be based on the combined score of both stages.

The results of the written examination were declared in May 2023. This is where the controversy started. When category-wise shortlists were prepared for the typing test, it was found that the general category cut-off was around 196 marks. But the cut-offs for several reserved categories, such as Scheduled Castes, Other Backwards Classes, Most Backwards Classes and Economically Weaker Sections, were much higher. In some categories, the cut-off crossed even 230 marks.

As a result, several candidates from reserved categories who had scored more than the General category cut-off were not shortlisted for the typing test. They failed to meet the much higher cut-off fixed for their own category. At the same time, General category candidates with lower scores were allowed to appear for the typing test.

This led to serious grievances. The affected candidates argued that they were being unfairly blocked from the recruitment process despite having better marks than many others who were allowed to move ahead.

Challenge before the Rajasthan High Court

These candidates approached the Rajasthan High Court, arguing that the shortlisting method treated the General (Open) category as if it were meant only for unreserved candidates. They said this violated their right to equality and equal opportunity under Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution.

The High Court examined the issue in detail and agreed with the candidates. It held that while category-wise shortlisting is not illegal by itself, the stage at which it is applied and the way it is done are extremely important.

The court ruled that if a reserved category candidate scores above the general cut-off without using any relaxation or concession, then that candidate must be considered in the General (Open) category at that level. Denying such candidates a chance was found to be unconstitutional.

High Court orders fresh merit list

The Rajasthan High Court ordered that the entire merit list be reworked. It directed the authorities to first prepare the General (Open) category list on merit. This list must include reserved category candidates who scored above the general cut-off, provided they had not taken any reservation-related benefits, the court said.

The court also ordered that candidates who were excluded from the typing test be given an opportunity to appear in it. The High Court clarified that it was not abolishing reservation, nor was it saying that category-based shortlisting is always wrong. The problem lay in using caste labels too early in the selection process in a way that harmed meritorious candidates.

Questions raised before the Supreme Court

Unhappy with this decision, the Rajasthan High Court administration moved the Supreme Court. It argued that the adjustment of reserved category candidates into the General category should happen only at the final stage of selection, not during shortlisting for the second stage. Doing it earlier, it claimed, would give such candidates a “double benefit”.

Another argument was that past court rulings on this issue applied only to final selection and not to intermediate stages like shortlisting. The administration also said that candidates who took part in the recruitment process could not challenge it later, since they had accepted its rules by participating.

Supreme Court rejects “double benefit” argument

The Supreme Court firmly rejected all these arguments. It acknowledged that generally, candidates cannot challenge a selection process after taking part in it. However, it said this rule is not absolute.

The court pointed out that while the recruitment advertisement mentioned category-wise lists, it never said that meritorious reserved category candidates would be barred from the General category. Therefore, candidates were well within their rights to challenge an unfair interpretation of the rules.

On the issue of double benefit, the court made its position very clear. It said that merely mentioning a reserved category in the application form does not automatically mean that the candidate is taking reservation benefits. It only gives the candidate an option to compete within their category if needed.

The court described the fear of “double benefit” as based on a misunderstanding. It said there is no rule that a reserved category candidate enjoys reservation advantages at every stage of a multi-level selection process.

Meaning of the “open” category clarified

In one of the most significant observations, the Supreme Court explained the meaning of the word “open”. It said open posts are not attached to any caste, class, tribe or gender. Any suitable candidate can be appointed to them based purely on merit.

The court added that if a reserved category candidate, through hard work alone and without any concessions, scores higher than both reserved and general category candidates in a screening or preliminary exam, then that candidate must be allowed to appear in the next stage. There is no question of “migration” in such cases.

However, the court also clarified that this ruling applies to this particular recruitment. If recruitment rules clearly state something else, those rules would prevail.

Important caveat by the Supreme Court

While upholding the High Court’s decision, the Supreme Court also pointed out a practical limitation. It said that sometimes a reserved category candidate who appears in the General merit list may find their choices limited later. This could happen if certain posts or services are specifically marked for reserved quotas.

In such cases, being treated as a general category candidate may restrict the options available, even though the candidate performed better.

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeals but advised the High Court to ensure that employees already appointed are not removed while implementing the order.

Why this judgment matters

This decision goes far beyond one recruitment exam in Rajasthan. For years, social media has been flooded with screenshots claiming that SC, ST or OBC cut-offs are higher than general cut-offs, often to spark arguments about merit. This judgment explains exactly why such situations arise and why they are legally valid.

See this too

— Nethrapal (@nethrapal) November 4, 2025

General Cutoff less than OBC SC ST Cutoff- Kya bhai merit kahan hai merit https://t.co/mZeCNyw0zM pic.twitter.com/bsWVREq20D

The court made it clear that the key factor is whether a candidate used any reservation-related benefits. If a reserved category candidate took age relaxation, extra attempts or physical concessions, then even a high score cannot place them in the General category. Such candidates must be counted within their own category.

Because many reserved category candidates do use these benefits, they are excluded from the general merit list even after scoring well. A higher number of candidates using the category-specific relaxations to appear for exams pushes up the reserved category cut-off, sometimes making it higher than the general cut-off.

In simple terms, the judgment reinforces that reservation is not about unfair advantage or punishment. It is about creating balance and inclusion while respecting merit. A higher cut-off in reserved categories is not a flaw in the system but proof that it is working as designed under the Constitution.