Was the ‘Dhurandhar’ qawwali ‘Na to Caravan ki talash hai’ written by a Pakistani? No, it was written by Bollywood’s Sahir Ludhianwi for film Barsaat ki Raat

The Qawwali “Na to caravan ki talash hai, na to humsafar ki talash hai” used in the Bollywood blockbuster film Dhurandhar is similar to the qawwali filmed in the 1960 Hindi film “Barsaat Ki Raat”. As per the information available on Apple Music about the official documents and credits of the song, the lyrics were written by Sahir Ludhianvi and composed by Roshan. This qawwali features the voices of several singers and was recorded as a group performance. Its singers included Manna Dey, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Sudha Malhotra, and SD Batish. According to records, this is its first published and widely recognised film version. Based on this, it is said that the official film origin of this qawwali is linked to Indian cinema and Bollywood. Music labels and film archives clearly list the names of the writers, composers, and singers. Therefore, when questions like “who gets the credit?” arise, they are referring to the 1960 film “Barsaat Ki Raat.” However, Qawwali is not a classical or individual form but a shared, oral musical tradition, descended from the Sufi tradition, with roots in the Punjab region. This is why some music lovers and historians argue that the melody and sentiment of the qawwali “Barsaat Ki Raat” appear to be inspired by the Lahore-centred Sufi qawwali tradition. Often cited in this context is the qawwali “Na Toh Butkade Ki Talab Mujhe,” sung by Mubarak Ali Khan and Fateh Ali Khan in the 1950s. The song was written by Amir Sabri. However, there is a crucial distinction here. While the claims of inspiration or cultural similarity can be a matter of historical debate, there is no concrete, published audio or documentation available to prove that the full lyrics of “Na To Caravan Ki Talash Hai” were recorded and released in the same form before 1960. Therefore, similarities are not seen as evidence but as cultural influence. Such influences are common in oral traditions, but documentary evidence is necessary to establish credit. This song from “Barsaat Ki Raat” is not just a qawwali; it is a 13-minute-long song that begins with the Sufi and Nirgun traditions and progresses to the Bhakti movement. It offers glimpses of Radha-Krishna and Meera, then reaches Buddha’s Bodhi tree, and ultimately becomes a symbol of Christ’s compassion. Due to this, it is considered a cinematic document of the Ganga-Jamuni culture and India’s multi-religious cultural consciousness. Although Qawwali is extremely popular among music lovers in Pakistan and across the Indian subcontinent, its origin and composition are from India. The bottom line is that this qawwali may be part of a culturally shared heritage, as Sufi music’s roots predate the modern India-Pakistan border. However, when it comes to the song’s origin, authorship, and credit, available historical and filmic records clearly indicate that its authentic, published, and recognised origin comes from the 1960 Indian film “Barsaat Ki Ek Raat.” This is why, while acknowledging cultural sharing, the current debate often gives official credit to Indian cinema.

The Qawwali “Na to caravan ki talash hai, na to humsafar ki talash hai” used in the Bollywood blockbuster film Dhurandhar is similar to the qawwali filmed in the 1960 Hindi film “Barsaat Ki Raat”.

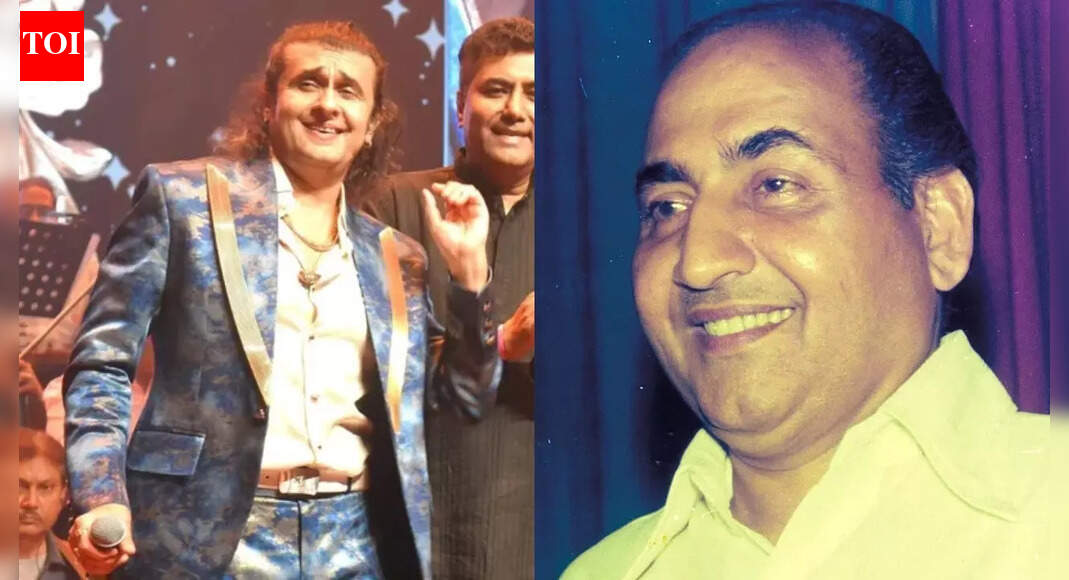

As per the information available on Apple Music about the official documents and credits of the song, the lyrics were written by Sahir Ludhianvi and composed by Roshan. This qawwali features the voices of several singers and was recorded as a group performance. Its singers included Manna Dey, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhosle, Sudha Malhotra, and SD Batish. According to records, this is its first published and widely recognised film version.

Based on this, it is said that the official film origin of this qawwali is linked to Indian cinema and Bollywood. Music labels and film archives clearly list the names of the writers, composers, and singers. Therefore, when questions like “who gets the credit?” arise, they are referring to the 1960 film “Barsaat Ki Raat.”

However, Qawwali is not a classical or individual form but a shared, oral musical tradition, descended from the Sufi tradition, with roots in the Punjab region. This is why some music lovers and historians argue that the melody and sentiment of the qawwali “Barsaat Ki Raat” appear to be inspired by the Lahore-centred Sufi qawwali tradition. Often cited in this context is the qawwali “Na Toh Butkade Ki Talab Mujhe,” sung by Mubarak Ali Khan and Fateh Ali Khan in the 1950s. The song was written by Amir Sabri.

However, there is a crucial distinction here. While the claims of inspiration or cultural similarity can be a matter of historical debate, there is no concrete, published audio or documentation available to prove that the full lyrics of “Na To Caravan Ki Talash Hai” were recorded and released in the same form before 1960. Therefore, similarities are not seen as evidence but as cultural influence. Such influences are common in oral traditions, but documentary evidence is necessary to establish credit.

This song from “Barsaat Ki Raat” is not just a qawwali; it is a 13-minute-long song that begins with the Sufi and Nirgun traditions and progresses to the Bhakti movement. It offers glimpses of Radha-Krishna and Meera, then reaches Buddha’s Bodhi tree, and ultimately becomes a symbol of Christ’s compassion. Due to this, it is considered a cinematic document of the Ganga-Jamuni culture and India’s multi-religious cultural consciousness.

Although Qawwali is extremely popular among music lovers in Pakistan and across the Indian subcontinent, its origin and composition are from India.

The bottom line is that this qawwali may be part of a culturally shared heritage, as Sufi music’s roots predate the modern India-Pakistan border. However, when it comes to the song’s origin, authorship, and credit, available historical and filmic records clearly indicate that its authentic, published, and recognised origin comes from the 1960 Indian film “Barsaat Ki Ek Raat.” This is why, while acknowledging cultural sharing, the current debate often gives official credit to Indian cinema.