PM Modi announces plans to open nuclear sector to private investors: Why the push for privatisation matters and what it means for India

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would open its tightly controlled nuclear sector to private players, it marked one of the most consequential economic and strategic decisions of the last few decades. This was not a routine policy update or a token reform designed for headlines. It was a structural shift, one that redefines how India views power, technology, risk, and national ambition. Speaking at the inauguration of Skyroot Aerospace’s Infinity Campus in Hyderabad, Modi consciously linked the future of India’s nuclear sector to the transformation already underway in India’s space ecosystem. He invoked the story of private space startups like Skyroot to make a broader point: innovation flourishes when monopoly dies. “We’ll open up the nuclear sector to the private sector soon,” Modi said. “This will strengthen opportunities in small modular and advanced reactors and nuclear innovations.” It was a short sentence with enormous strategic weight. Dismantling a 60-year-old state monopoly Since the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, India’s nuclear power sector has existed under a rigid state monopoly. Civilian nuclear generation was treated not as an economic frontier, but as an extension of national security infrastructure. Everything flowed through the Department of Atomic Energy and a set of highly centralised public sector units. Private enterprise was kept out by law, suspicion, and ideology. This was not just about safety concerns. It was about mindset. Post-Independence India inherited a deep mistrust of private capital in “strategic” sectors, thanks to Nehruvian socialism that equated state control with national interest. Modi’s announcement tears through this legacy. For the first time, the Indian state is publicly acknowledging that private innovation and private capital are not threats to sovereignty — they are tools of sovereignty. Why this reform matters Contrary to alarmist messaging, this is not about privatising nuclear weapons or handing over strategic assets to corporations. The reform targets civilian nuclear power, energy generation, reactor development, supply chains, engineering, research, and innovation, under strict regulatory supervision. The focus areas are telling. The government plans to develop Bharat Small Reactors, small modular reactors (SMRs), and advanced next-generation reactor technologies. These systems are not vanity projects. They represent the global future of nuclear power. SMRs, in particular, are considered revolutionary because they require less land, involve lower upfront capital, can be deployed faster, and are inherently safer due to modern passive cooling and containment systems. For a densely populated country like India, these features are not just attractive, they are essential. Private participation means more than just money. It means competition, speed, accountability, manufacturing depth, and integration with global innovation ecosystems. Why India cannot rely on old energy models anymore India’s energy reality today is a strategic contradiction. The country wants rapid industrial expansion, data centre growth, electric mobility, semiconductor fabrication, and AI infrastructure. All of this requires uninterrupted, round-the-clock, high-quality power. Coal continues to dominate, but it brings environmental pressure and global criticism. Solar and wind are expanding rapidly, but they are intermittent and land-hungry. Hydropower is geographically limited. Oil and gas are mostly imported, exposing India to global price shocks and geopolitical pressure points like the Strait of Hormuz. This is where nuclear power becomes not just an option, but a necessity. Nuclear energy is clean, reliable, and scalable. Unlike renewables, it provides stable base-load power. Unlike fossil fuels, it doesn’t chain India’s economy to foreign suppliers. Modi’s long-stated ambition of reaching 100 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047 is not symbolic — it is foundational to India’s dream of becoming a developed nation. Without a massive nuclear push, “Viksit Bharat” remains an energy fantasy. The lessons from the Space sector Modi deliberately chose the setting of a private space startup to make this announcement. India’s space sector for decades was housed entirely within ISRO. It produced historic achievements, but at a pace and scale controlled by bureaucratic limitations. The opening of the space sector to private players changed that. Startups like Skyroot, Agnikul and others brought agility, speed, risk-taking, and investor capital. Suddenly, India wasn’t just a government space power, it was becoming a commercial space hub. Modi’s message was simple: if private participation could democratise and accelerate space innovation, there is no reason nuclear should remain trapped in 20th-century command-and-control structures. The Atomic Energy Bill, 2025: Turning intent into law This announcement i

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would open its tightly controlled nuclear sector to private players, it marked one of the most consequential economic and strategic decisions of the last few decades. This was not a routine policy update or a token reform designed for headlines. It was a structural shift, one that redefines how India views power, technology, risk, and national ambition.

Speaking at the inauguration of Skyroot Aerospace’s Infinity Campus in Hyderabad, Modi consciously linked the future of India’s nuclear sector to the transformation already underway in India’s space ecosystem. He invoked the story of private space startups like Skyroot to make a broader point: innovation flourishes when monopoly dies.

“We’ll open up the nuclear sector to the private sector soon,” Modi said. “This will strengthen opportunities in small modular and advanced reactors and nuclear innovations.”

It was a short sentence with enormous strategic weight.

Dismantling a 60-year-old state monopoly

Since the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, India’s nuclear power sector has existed under a rigid state monopoly. Civilian nuclear generation was treated not as an economic frontier, but as an extension of national security infrastructure. Everything flowed through the Department of Atomic Energy and a set of highly centralised public sector units. Private enterprise was kept out by law, suspicion, and ideology.

This was not just about safety concerns. It was about mindset. Post-Independence India inherited a deep mistrust of private capital in “strategic” sectors, thanks to Nehruvian socialism that equated state control with national interest.

Modi’s announcement tears through this legacy.

For the first time, the Indian state is publicly acknowledging that private innovation and private capital are not threats to sovereignty — they are tools of sovereignty.

Why this reform matters

Contrary to alarmist messaging, this is not about privatising nuclear weapons or handing over strategic assets to corporations. The reform targets civilian nuclear power, energy generation, reactor development, supply chains, engineering, research, and innovation, under strict regulatory supervision.

The focus areas are telling. The government plans to develop Bharat Small Reactors, small modular reactors (SMRs), and advanced next-generation reactor technologies. These systems are not vanity projects. They represent the global future of nuclear power.

SMRs, in particular, are considered revolutionary because they require less land, involve lower upfront capital, can be deployed faster, and are inherently safer due to modern passive cooling and containment systems. For a densely populated country like India, these features are not just attractive, they are essential.

Private participation means more than just money. It means competition, speed, accountability, manufacturing depth, and integration with global innovation ecosystems.

Why India cannot rely on old energy models anymore

India’s energy reality today is a strategic contradiction. The country wants rapid industrial expansion, data centre growth, electric mobility, semiconductor fabrication, and AI infrastructure. All of this requires uninterrupted, round-the-clock, high-quality power.

Coal continues to dominate, but it brings environmental pressure and global criticism. Solar and wind are expanding rapidly, but they are intermittent and land-hungry. Hydropower is geographically limited.

Oil and gas are mostly imported, exposing India to global price shocks and geopolitical pressure points like the Strait of Hormuz.

This is where nuclear power becomes not just an option, but a necessity.

Nuclear energy is clean, reliable, and scalable. Unlike renewables, it provides stable base-load power. Unlike fossil fuels, it doesn’t chain India’s economy to foreign suppliers. Modi’s long-stated ambition of reaching 100 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047 is not symbolic — it is foundational to India’s dream of becoming a developed nation.

Without a massive nuclear push, “Viksit Bharat” remains an energy fantasy.

The lessons from the Space sector

Modi deliberately chose the setting of a private space startup to make this announcement. India’s space sector for decades was housed entirely within ISRO. It produced historic achievements, but at a pace and scale controlled by bureaucratic limitations.

The opening of the space sector to private players changed that. Startups like Skyroot, Agnikul and others brought agility, speed, risk-taking, and investor capital. Suddenly, India wasn’t just a government space power, it was becoming a commercial space hub.

Modi’s message was simple: if private participation could democratise and accelerate space innovation, there is no reason nuclear should remain trapped in 20th-century command-and-control structures.

The Atomic Energy Bill, 2025: Turning intent into law

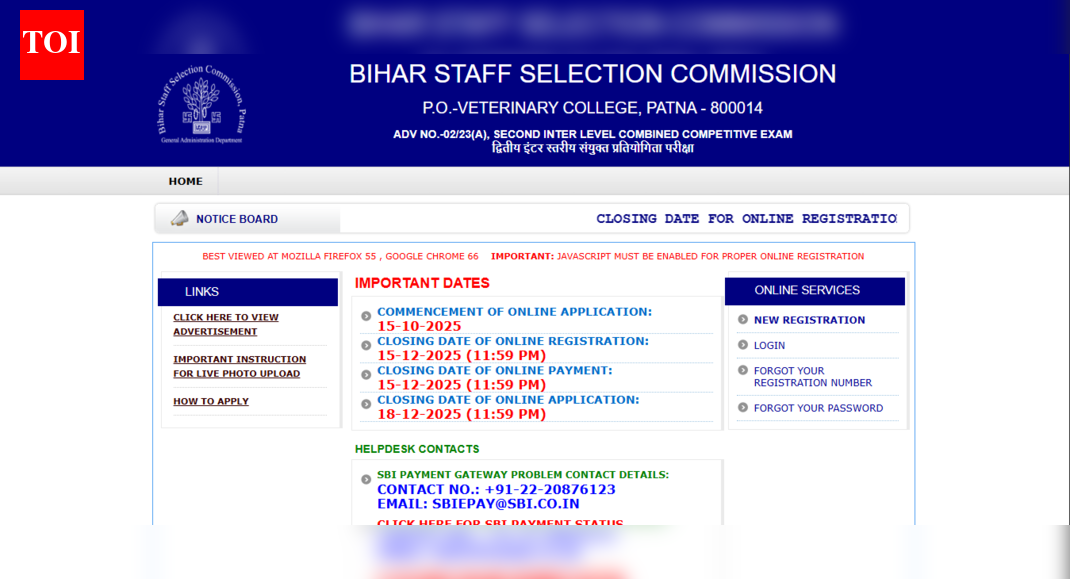

This announcement is not merely rhetorical. It is anchored in concrete legislative planning. The government is preparing to table the Atomic Energy Bill, 2025 in the Winter Session of Parliament.

This Bill, along with amendments to the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLND) Act, 2010, will create the legal architecture that allows private companies to enter the sector without being crushed by legal and financial uncertainty.

This is a crucial point. No serious private investor will touch nuclear projects if liability laws are vague, punitive, or politically weaponisable. By restructuring these laws, the government is signalling that it is serious about long-term ecosystem building, not just symbolic reform.

Energy as sovereignty, not just infrastructure

The deeper story here is not electricity. It is sovereignty.

In the 21st century, energy is power in the most literal sense. Countries that control reliable, scalable energy are not just richer; they are harder to threaten, harder to sanction, harder to coerce.

By expanding domestic nuclear capacity, India reduces dependence on:

– Imported hydrocarbons

– Western-controlled climate financing

– Foreign technology chokepoints

This is strategic autonomy through infrastructure. And we have already witnessed in the last few months as relationship between India and the US strained over Russian oil purchases. While the US itself trades with Russia for its energy requirements, it’s pressure on other nations, in this case, India, shows the need for New Delhi to explore alternative measures to ensure there are multiple avenues for the country to fulfil the energy needs of its 1.4 bn people.

At the same time when the world is fragmenting into tech blocs and economic alliances, India is trying to ensure it never becomes a hostage to other people’s power grids.

The Economic Multiplier Effect

Opening the nuclear sector can create a massive secondary ecosystem. It means thousands of high-skilled engineering jobs, domestic manufacturing of specialised components, new research institutions, advanced material science development, and export possibilities.

A mature nuclear industrial base doesn’t just produce electricity. It produces scientific capacity, strategic depth, and technological prestige.

Countries that master nuclear technology don’t just sell power plants, they sell partnerships.

The Bigger Modi Strategy

This move fits cleanly into a broader pattern. Semiconductor push. Defence indigenisation. Space privatisation. Digital public infrastructure. Now nuclear.

What ties them together is not ideology but sovereignty through capability. Modi isn’t trying to make India comfortable. He’s trying to build a resilient India.

By 2047, when India marks 100 years of Independence, the countries that will dominate the world won’t just be the richest. They will be the ones with secure energy, secure chips, secure data, and secure defence production.

Nuclear reform is one pillar of that architecture.

Opening India’s nuclear sector to private players is not a gamble. It is a delayed correction. The real risk was not reform. The real risk was staying trapped in a system built for a different century, with different ambitions, and much lower expectations.

Modi’s announcement doesn’t weaken the state. It repositions it from monopolistic controller to strategic regulator and enabler. India does not need to fear private capital in nuclear energy. It needs to fear energy weakness.

And with this move, it is choosing strength.