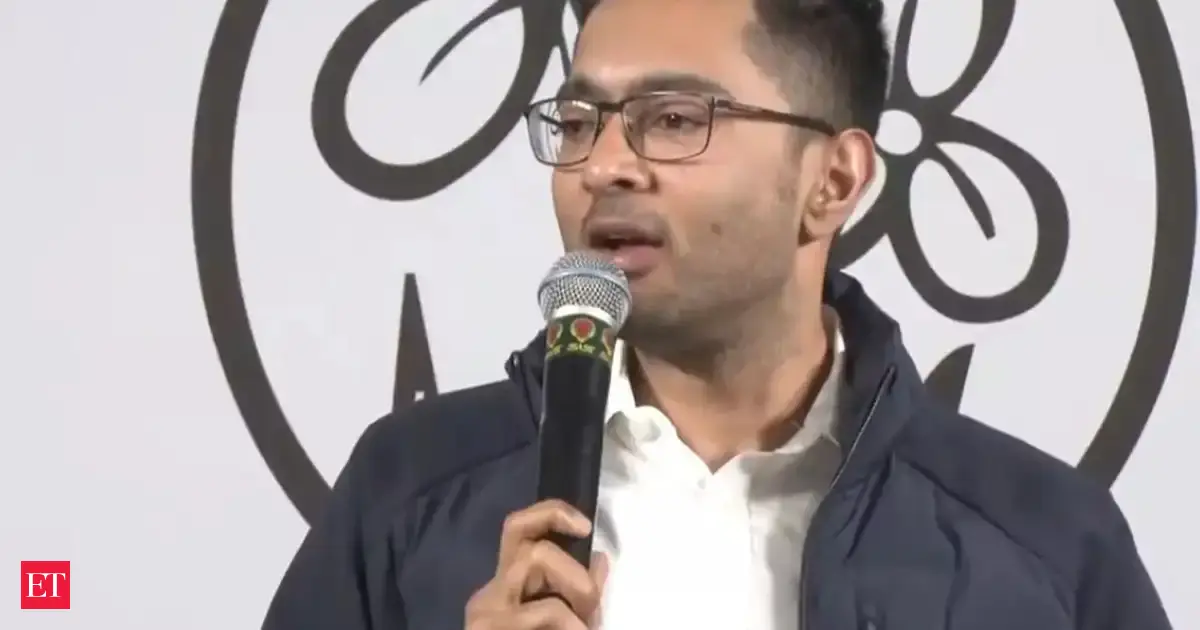

Rich want over-regulation to make the poor invisible: Zomato founder Deepinder Goyal opens up on gig work debate; responds to 10-minute delivery, career progress and other concerns

Amid the debate over the working conditions of gig workers, Deepinder Goyal, founder of Zomato and Blinkit, have addressed the issues raised by delivery partners and others through a series of posts on X. The debate was raised after a nationwide strike was called by delivery partners associated with platforms like Zomato, Blinkit, Swiggy, Zepto, Amazon, and Flipkart on 31st December 2025, following a flash strike on 25th. Deepinder Goyal in his posts defended the gig economy, clarified misconceptions about 10-minute deliveries, explained benefits available to delivery partners, and attributed disruptions to a small group of “miscreants.” Delivery Workers’ Strikes and Demands The strikes were organized by unions such as the Gig and Platform Service Workers Union (TGPWU) and the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT). The actions were framed as protests against an “exploitative” system, with workers demanding systemic changes to improve dignity, protection, and fairness. A flash strike on December 25, 2025 reportedly caused 50-60% service disruptions in several cities, including metros and tier-2 areas like Gurugram, as workers halted operations to draw attention to ongoing issues. This was followed by a December 31, 2025 nationwide strike called for New Year’s Eve to maximize impact during peak demand. Unions claimed broad participation; however, it was found that only a handful of workers stopped working. Goyal also said that platforms like Zomato and Blinkit saw minimal disruption. Workers demanded fair and transparent pay, protesting falling earnings due to low per-order payouts, rising fuel costs, and lack of holiday incentives. They are also demanding fixed minimum wages and an end to opaque algorithms that reduce incentives. Safety and working conditions were major concerns, with criticism on “ultra-fast” delivery models like 10-minute promises, which workers claimed increase accident risks by encouraging rushed driving. Demands included scrapping these targets, providing better insurance, rest breaks, and protections against long working hours. Job security and grievance redressal were also highlighted, with complaints about arbitrary account suspensions without due process, weak support systems, and lack of social security such as pensions and health benefits. unions called for national policies on gig worker rights, including background checks and fair termination processes. They sought an end to exploitative practices, such as pressure from platforms to meet unsafe targets, and recognition of gig work as deserving of labour protections. Deepinder Goyal’s Response to the Debate On 1st and 2nd January, 2026, Goyal posted a series of updates on X, directly addressing the strikes, gig worker conditions, and misconceptions about Blinkit’s 10-minute delivery model. He emphasized the system’s fairness and voluntary nature, explaining how the delivery platforms generate employment. Regarding the strikes and gig worker treatment, Goyal reported that Zomato and Blinkit achieved record highs on new years’ eve, with over 7.5 million orders delivered by more than 450,000 partners to 6.3 million customers, unaffected by strike calls. He credited local law enforcement for managing a small number of “miscreants”, about 0.1% of workers who intimidated others by snatching parcels, assaulting them, or threatening vehicle damage. He said that these agitators are former workers terminated for fraud, theft, impersonation, or absconding with cash, possibly instigated by “politically motivated individuals” seeking media attention, and argued that most delivery partners rejected the strike, choosing “honest work and progress.” Defending the gig economy, he noted it as one of India’s largest job creators, with long-term benefits like stable incomes enabling education for workers’ children, and urged sceptics not to fall for “narratives pushed by vested interests,” asserting that an unfair system wouldn’t attract and retain so many voluntary participants. Responding to specific queries, Goyal confirmed all workers have medical and life insurance, and hiring requires a valid driver’s license and background check. Responding to query on ‘career progression’, he described gig work as temporary, saying it is not a career with progression, with 65% annual attrition. “This is not a permanent job for anyone. Most people do this for a few months in a year and move on to something more permanent,” he said. Importantly, he also stated there are no penalties for late deliveries, acknowledging real-world delays like traffic. On the 10-minute delivery model, which strikers linked to safety risks, Goyal explained that it is enabled by operational efficiency rather than rider pressure. He explained that delivery partners are not even shown the time, and it is based on the distance from the store to the customer’s location. As Blinkit most mostly delivers grocery items, and such store

Amid the debate over the working conditions of gig workers, Deepinder Goyal, founder of Zomato and Blinkit, have addressed the issues raised by delivery partners and others through a series of posts on X. The debate was raised after a nationwide strike was called by delivery partners associated with platforms like Zomato, Blinkit, Swiggy, Zepto, Amazon, and Flipkart on 31st December 2025, following a flash strike on 25th.

Deepinder Goyal in his posts defended the gig economy, clarified misconceptions about 10-minute deliveries, explained benefits available to delivery partners, and attributed disruptions to a small group of “miscreants.”

Delivery Workers’ Strikes and Demands

The strikes were organized by unions such as the Gig and Platform Service Workers Union (TGPWU) and the Indian Federation of App-based Transport Workers (IFAT). The actions were framed as protests against an “exploitative” system, with workers demanding systemic changes to improve dignity, protection, and fairness.

A flash strike on December 25, 2025 reportedly caused 50-60% service disruptions in several cities, including metros and tier-2 areas like Gurugram, as workers halted operations to draw attention to ongoing issues. This was followed by a December 31, 2025 nationwide strike called for New Year’s Eve to maximize impact during peak demand. Unions claimed broad participation; however, it was found that only a handful of workers stopped working. Goyal also said that platforms like Zomato and Blinkit saw minimal disruption.

Workers demanded fair and transparent pay, protesting falling earnings due to low per-order payouts, rising fuel costs, and lack of holiday incentives. They are also demanding fixed minimum wages and an end to opaque algorithms that reduce incentives. Safety and working conditions were major concerns, with criticism on “ultra-fast” delivery models like 10-minute promises, which workers claimed increase accident risks by encouraging rushed driving. Demands included scrapping these targets, providing better insurance, rest breaks, and protections against long working hours.

Job security and grievance redressal were also highlighted, with complaints about arbitrary account suspensions without due process, weak support systems, and lack of social security such as pensions and health benefits. unions called for national policies on gig worker rights, including background checks and fair termination processes. They sought an end to exploitative practices, such as pressure from platforms to meet unsafe targets, and recognition of gig work as deserving of labour protections.

Deepinder Goyal’s Response to the Debate

On 1st and 2nd January, 2026, Goyal posted a series of updates on X, directly addressing the strikes, gig worker conditions, and misconceptions about Blinkit’s 10-minute delivery model. He emphasized the system’s fairness and voluntary nature, explaining how the delivery platforms generate employment.

Regarding the strikes and gig worker treatment, Goyal reported that Zomato and Blinkit achieved record highs on new years’ eve, with over 7.5 million orders delivered by more than 450,000 partners to 6.3 million customers, unaffected by strike calls. He credited local law enforcement for managing a small number of “miscreants”, about 0.1% of workers who intimidated others by snatching parcels, assaulting them, or threatening vehicle damage. He said that these agitators are former workers terminated for fraud, theft, impersonation, or absconding with cash, possibly instigated by “politically motivated individuals” seeking media attention, and argued that most delivery partners rejected the strike, choosing “honest work and progress.”

Defending the gig economy, he noted it as one of India’s largest job creators, with long-term benefits like stable incomes enabling education for workers’ children, and urged sceptics not to fall for “narratives pushed by vested interests,” asserting that an unfair system wouldn’t attract and retain so many voluntary participants.

Responding to specific queries, Goyal confirmed all workers have medical and life insurance, and hiring requires a valid driver’s license and background check. Responding to query on ‘career progression’, he described gig work as temporary, saying it is not a career with progression, with 65% annual attrition. “This is not a permanent job for anyone. Most people do this for a few months in a year and move on to something more permanent,” he said.

Importantly, he also stated there are no penalties for late deliveries, acknowledging real-world delays like traffic.

On the 10-minute delivery model, which strikers linked to safety risks, Goyal explained that it is enabled by operational efficiency rather than rider pressure. He explained that delivery partners are not even shown the time, and it is based on the distance from the store to the customer’s location. As Blinkit most mostly delivers grocery items, and such stores are located in almost every location in a city, the app is able to promise 10 minute delivery, he explained.

One more thing. Our 10 minute delivery promise is enabled by the density of stores around your homes. It’s not enabled by asking delivery partners to drive fast. Delivery partners don’t even have a timer on their app to indicate what was the original time promised to the…

— Deepinder Goyal (@deepigoyal) January 1, 2026

Goyal stated that orders are picked and packed in 2.5 minutes at dense store networks near customers, with riders then covering an average of under 2 km in about 8 minutes at a safe 15 kmph. He said that riders have no timer visible in their app showing the customer’s promised time, removing any incentive to rush. He said that he understands why everyone thinks that 10-minute delivery must be risking lives, adding that it is indeed hard to imagine the sheer complexity of the system design which enables quick deliveries.

Addressing traffic violations, Goyal argued it is a societal issue in India, not unique to delivery workers, and attributed public bias to uniforms making them noticeable while non-uniformed violators go unremembered. He encouraged users to speak directly with riders for honest insights into why they choose gig work, suggesting it humbles assumptions of exploitation, and while admitting no system is perfect, maintained it is “far from what it is being portrayed on social media.”

Deepinder Goyal also confirmed that the riders keep 100% of the tips given by customers, saying it is over and above the wages that range from ₹25,000 to ₹30,000 a month. “All tips get passed on to our riders as is, without any deductions (even no deductions for payment gateway charges),” he said. However he added that tips are a small part of a rider’s overall income, as India does not a culture of paying big tips like in the West.

Tips are over and above the wages (~25-30k per month) that we quote.

— Deepinder Goyal (@deepigoyal) January 2, 2026

Having said that, tips are a small part of a rider's overall income. We aren't a good tipping economy.

All tips get passed on to our riders as is, without any deductions (even no deductions for payment gateway… https://t.co/CPkSGAGQr0

Emphasizing on the role of the sector in generating jobs, Goyal said that gig workers is one of the largest organised job creation engines in India, adding that they provide insurance, fair, timely and predictable wages.

Responding to calls for regulation of the sector, he said, “Gig doesn’t need more regulation, it needs less regulation. It will bring more people into the fold, who will be able to earn some money, upskill themselves and later join India’s organised workforce. Not to mention, consistently send their kids to school – which will fundamentally change the fabric of our nation one generation later.”

In his last comments on the issue, Deepinder Goyal offered a broader sociological perspective on the gig economy debate, calling it a historical shift that has made the labour of the working class visible to the affluent at an unprecedented scale, thereby evoking discomfort and guilt among consumers. He said that for centuries, class divides kept the labour of the poor invisible to the rich, but gig economy has brought them face to face.

He argued that for centuries, class divides kept workers invisible, allowing the wealthy to consume without confronting the human cost, but gig platforms now bring direct, repeated interactions that personalise inequality, such as seeing a delivery partner’s exhaustion while receiving a luxury meal.

“This is the first time in history at this scale that the working class and consuming class interact face-to-face, transaction after transaction. And that discomfort with our own selves is why we are uncomfortable about the gig economy. We want these people to look our part, so that the guilt we feel while taking orders from them feels less,” he wrote.

Goyal contended that calls to ban or over-regulate gig work stem not from genuine concern for dignity but from a desire to restore this invisibility of the poor. He warned that such actions would eliminate livelihoods without creating better alternatives, pushing workers back into unregulated informal sectors.

Goyal said, “Over-regulate it until the model breaks, and you achieve the same outcome through paperwork instead of slogans: the work evaporates, prices rise, demand collapses, and the people we claim to protect are the first to lose income.”

“The rich get their old comfort back. Convenience returns without faces. Guilt dissolves. We go back to clean abstractions and moral posturing from a distance. The poor don’t become safer, they become invisible again: back in cash economies, back in backrooms, back in shadows where regulation rarely reaches and dignity isn’t even debated,” he further stated.

Goyal advocated using this visibility-driven discomfort as a catalyst for continuous improvements, positioning the gig economy as progress toward addressing systemic issues rather than a return to ignorant complacency.